Six characters in search of a play

Even with deep thoughts and beguiling music, "Choir Boy" never fully coalesces into a successful drama

Choir Boy, the work by playwright Tarell Alvin McCraney now on offer at Shotgun Players, has all the makings of a wonderful play. It has a compelling setting — a historically African American private high school for boys — and a first-rate ensemble cast. It has plenty of music, beautifully sung both individually and chorally by the six students who play out their personal struggles in the school’s choir. And it has not one but two dexterously interleaved themes — about history and the salutary role of music — that intersect in the character of Pharus (William Schmidt, in a vibrant and multifaceted performance), a gifted but conflicted gay singer who takes over the leadership of the chorus in his senior year.

What it doesn’t quite have is a play.

For that, McCraney would have had to conjure up an array of fully human figures who interact in recognizably human ways. But he’s so busy prodding the six students and two adults (a Black headmaster and a white teacher) to say and do the things he wants them to say and do that very little onstage feels authentic. Instead, Choir Boy employs the bluntly reductive dramaturgy of a television sitcom, in which conflict is sketched in implausible bursts of feeling and overreaction, then swiftly resolved in time for the commercial break.

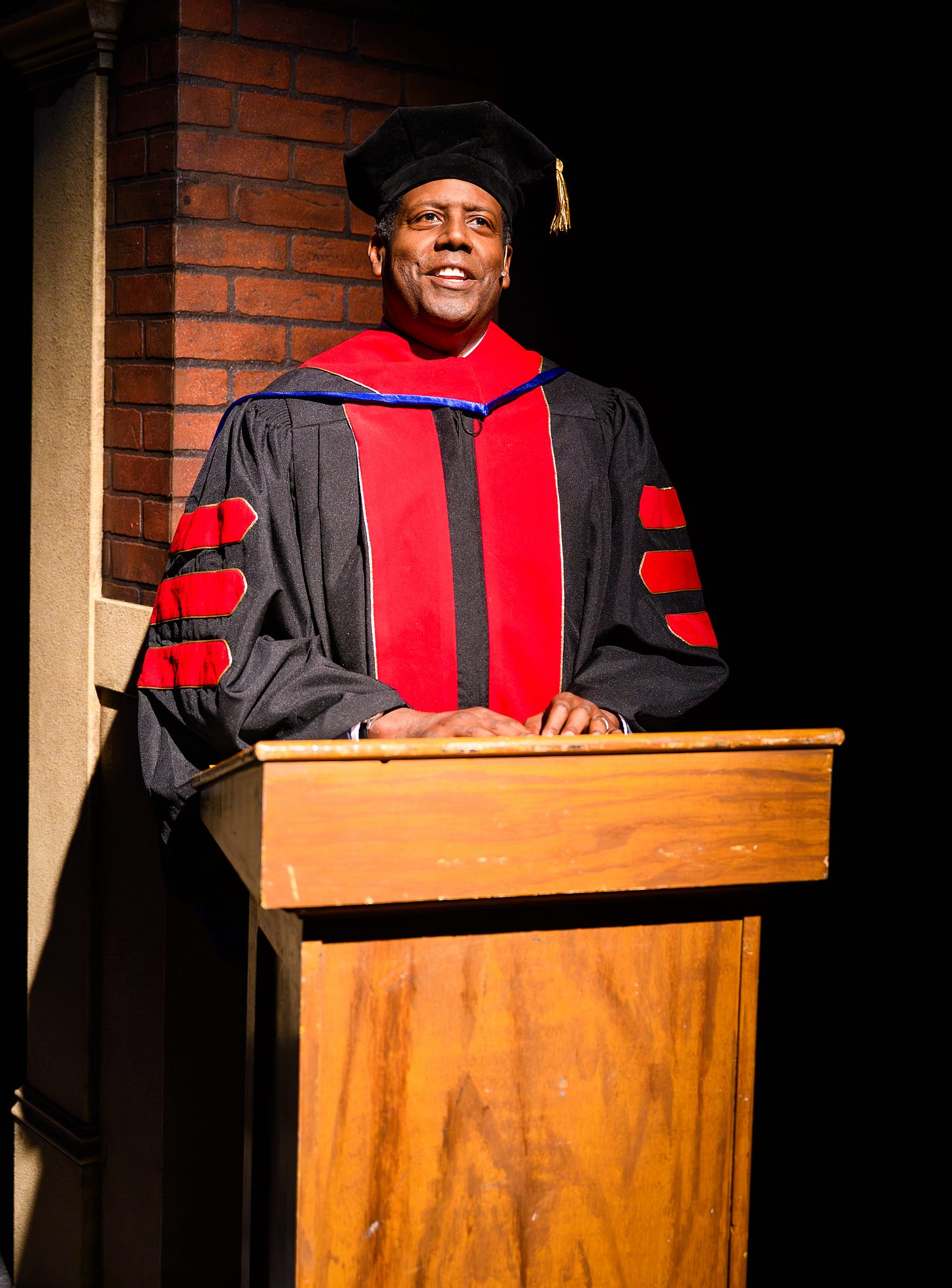

It’s a play in which a teacher might say, out of the blue, “That does it, I’m cancelling the chorus gala!” and then immediately back down when students exclaim, “But you can’t do that!” The headmaster (played with stoic grace by Fred Pitts) is meant to be a figure of steely authority, but he spends a lot of time threatening disciplinary measures and then not following through. In one extended, bewildering sequence, the chorus teacher assigns each student to prepare and sing a song that was important to their parents. Why? Who can say. They do it, and the drama moves on as if nothing had happened. When the curtain comes down at the end of two hours, the stage is littered with half a dozen threads that never wound up leading anywhere.

There’s no mystery about the dual concerns operating at the heart of Choir Boy. McCraney wants to explore the parallels between historical slavery and contemporary homophobia, and to celebrate music’s critical role in helping to negotiate both systems of oppression. That much becomes clear in the piece’s most riveting sequence, in which Pharus delivers an impassioned soliloquy in the middle of a class on critical thinking (or something — the exact focus of this all-important class is one of several junctures at which McCraney’s writing becomes vague). Pharus has a theory about spirituals, which is that it’s foolish to regard them as literal coded messages for runaway slaves heading north. Rather, he insists, the songs served as a gateway to a realm of transcendent freedom, just as choir music allows him to escape the homophobia that keeps him in chains.

It's a profound conceit, one that ties the strands of the piece together as deftly as they’re going to be, and it’s cast in a stretch of soaring, eloquent rhetoric that keeps you hanging on every word. But it’s also utterly untheatrical. Pharus simply stands up when called on in class, and begins to orate off the cuff like an American Demosthenes. If he’s been working on this thesis all along — either the underlying ideas or the actual framing — the audience hasn’t seen any evidence of it. Pharus’ speech lands full-blown on the narrow stage, an op-ed in all but its external trappings. Small wonder the other boys respond with hostility and unease.

For all its dramatic shortcomings, though, Choir Boy often skates through on the strength of its musical splendors, with music direction by Daniel Alley and foot-stomping choreography by AeJay Antonis Marquis. The robust blend of voices and the performers’ sinuous phrasing in one number after another (largely spirituals, with a few pop songs sprinkled into the mix) usher the audience into a world of emotion and hope far richer than anything in the boys’ mundane interactions — just as Pharus promised.

Choir Boy: Shotgun Players, through Oct. 26. www.shotgunplayers.org.

Elsewhere:

Lily Janiak, San Francisco Chronicle: “Pharus is very much a human vessel, and [McCraney’s] play is interested in what happens when that humanity becomes inconvenient for his institution.”

Steve Murray, Broadway World: “Choir Boy contains powerful emotional moments of tension, bonding, and humor.”

Joseph Mutti, Theatrius: “Choir Boy is a raucous, fast-moving musical revelation of what it means to be gay in an African American religious environment.”

Who’s afraid of Zachary Woolfe?

A friend alerted me to this gossipy item in the New York Post — which of course I would never have seen otherwise — about an incident in which Peter Gelb, the longtime boss of the Metropolitan Opera, uttered a public cry of dismay about New York Times music critic Zachary Woolfe. Gelb evidently got his knickers in a twist because Woolfe had had the temerity to write a negative review of Jeanine Tesori and George Brant’s Grounded, which opened the Met’s new season.

It couldn’t be that Woolfe’s review was intended to assess the piece on its merits, as the critic perceived them. And it’s impossible to believe that an opera Gelb knew to be “a brilliant work…[with] a brilliant story” could have been perceived by a different observer as “bloodless” or “faceless and bland.” No, no — there was clearly an “agenda” at work. In Gelb’s conspiracy-riddled world, Woolfe and other critics (“not all critics, some critics,” he reportedly added) are on a mission to champion the pieces they like and levy criticism at the pieces they don’t like. To which one can only reply, “Um…yes?”

This episode is too minor in the scheme of things to raise a fuss about. It’s really just a case of the New York Post stirring shit. But if you’ve been around the arts world for any period of time, it’s the kind of episode that comes around not only with predictable regularity, but with a depressing lack of inventiveness from one incarnation to the next. It’s like that quote about “young people today no longer respect their elders” that turns out to date from the Babylonian Empire, as evidence that things never change. For as long as there have been arts administrators and critics, the former have been whining about the latter in the exact same terms: Of course they’re free to write what they want, but if they criticize me or my company they’re doing it wrong. That’s where things become, as Gelb reportedly put it, “troublesome.”

I mean, I get it. It must be frustrating to devote all that hard work and money and institutional risk to a season-opening premiere, only to have someone come along and take a whack at it in the paper. But Gelb isn’t a newbie; he knows how this game is played. You put on a brave face, you take your lumps, and in the privacy of your own home you take out your Zachary Woolfe effigy and stick pins in it until the pain subsides.

Elsewhere

• Earlier this month, Gramophone magazine gave Michael Tilson Thomas its Lifetime Achievement Award, an honor that could not possibly have been more merited. I had the privilege of writing the magazine’s cover article about MTT’s manifold accomplishments and vast legacy. You can read it here.

• The San Francisco Opera has extended music director Eun Sun Kim’s contract for a second five-year term, through *gasp* 2031. Which means, as one observer has already noted, that at least one music director is sticking around the Bay Area.

Cryptic clue of the week

From Out of Left Field #237 by Henri Picciotto and me, sent to subscribers on Thursday:

“Stockpile money,” they say (5)

Last week’s clue:

Mark Cuban’s first error is uncommon (6)

Solution: SCARCE

Mark: SCAR

Cuban’s first [letter]: C

error: E [baseball]

uncommon: definition

Coming Up

• Oakland Symphony: Earlier this year, the young conductor Kedrick Armstrong was appointed as the orchestra’s music director, stepping into the post held for so long by the late, lamented Michael Morgan. For his first season opener, Armstrong has programmed three jazz-based works, by composers Allison Miller, John Santos, and Meklit, along with Nielsen’s Symphony No. 4, “The Inextinguishable.” Oct. 18, Paramount Theatre, Oakland. www.oaklandsymphony.org.

• San Francisco Symphony: I was enchanted by Esa-Pekka Salonen’s Cello Concerto when he introduced it to Bay Area audiences in a Berkeley concert five years ago with the Philharmonia Orchestra. Now we get to hear it with the hometown orchestra, and with principal cellist Rainer Eudeikis as soloist — an opportunity not to be missed. Beethoven and Debussy are also on the program, if you like those guys too. Oct. 18-20, Davies Symphony Hall. www.sfsymphony.org.

• Tristan and Isolde: Wagner’s mammoth operatic tale of love, betrayal and transfiguration returns to the San Francisco Opera for the first time in 18 years, with proven Wagnerians Simon O’Neill and Anja Kampe in the title roles. The cast also includes two promising debuts, from baritone Wolfgang Koch (Kurwenal) and mezzo-soprano Annika Schlicht (Brangäne), but the big draw is the chance to hear music director Eun Sun Kim in action on a big Wagner canvas. Oct. 19-Nov. 5, War Memorial Opera House. www.sfopera.com.

• Grounded: Don’t take Zachary Woolfe’s word about the new opera by composer Jeanine Tesori and librettist George Brant (see above), or Peter Gelb’s either. You can make up your own mind: Grounded opens the new season of the indispensable simulcast series The Met: Live in HD. Wherever you are, it’s on a movie screen not far from you. Oct. 19. www.metopera.org/season/in-cinemas/.

Um, doesn’t Peter Gelb get paid $2m a year to handle reviews in a professional manner? Ugh.