Blood and Gorey

A brilliant new song cycle by composer-performer Carla Kihlstedt was ghoulish, tender fun

Mahler’s 1904 orchestral song cycle Kindertotenlieder (Songs of the Death of Children) — whose contents are precisely what it says on the tin — is many things, but one thing it’s not is funny. 26 Little Deaths, the magnificent new song cycle by Carla Kihlstedt that opened San Francisco Performances’ PIVOT festival in Herbst Theatre on Wednesday, Jan. 29, is arguably just as probing a treatment of the same subject. But it’s also hilarious.

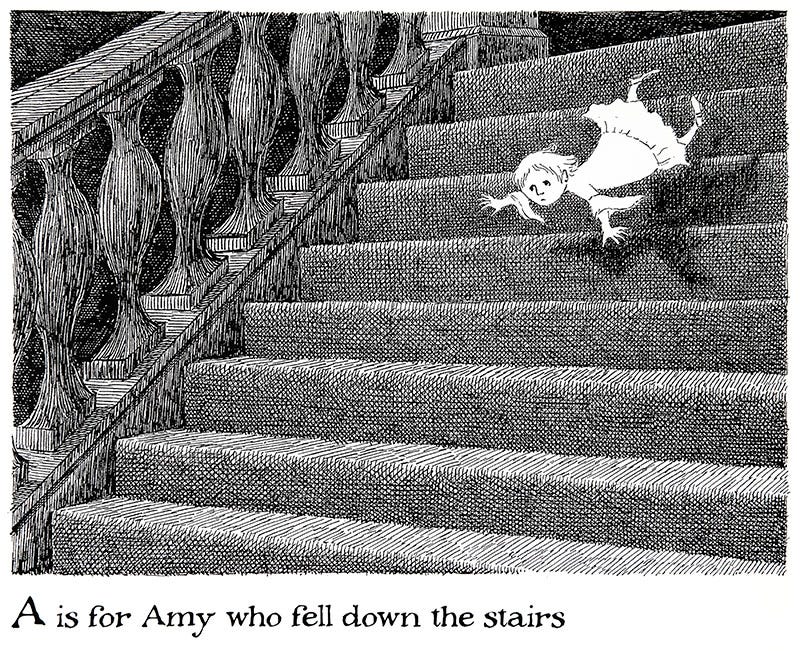

It's probably helpful at this juncture to note that Kihlstedt’s source material is The Gashlycrumb Tinies, Edward Gorey’s brilliant abecedarian picture book of underage demise. Ever since its publication in 1963, Gorey’s chillingly comic roster, presented in terse rhyming couplets and accompanied by his distinctively cross-hatched drawings, has been a nursery staple, helping to defang the subject of death for young readers (and their parents) by presenting it as deadpan farce. “A is for Amy who fell down the stairs/B is for Basil assaulted by bears,” the book begins, before continuing pairwise through “Y is for Yorick whose head was knocked in/Z is for Zillah who drank too much gin.” Some of the deaths are relatively recognizable (“drowned in a lake,” “consumed by a fire”). Others (“sucked dry by a leech,” “devoured by mice”) owe much to Gorey’s feverish imagination.

26 Little Deaths, which is due for a recording on the Cantaloupe label in March, isn’t simply a setting of Gorey’s text; there’s not nearly enough material there for the purpose. Rather, it’s a collection of short musical sketches — some purely instrumental, many more invested with new lyrics — that respond to each panel of the book. In a way, it’s a bit like Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, only crisper and far more mordant.

Also, unlike Mahler or Mussorgsky, Kihlstedt — who is a composer, singer, and violinist of equally dazzling abilities — rejoices in a wonderfully eclectic array of musical styles. 26 Little Deaths calls on a diverse array of instrumentation that allows for a wealth of different responses. This performance, conducted by PIVOT guest curator Gabriel Kahane, involved the Del Sol Quartet, Sandbox Percussion, pianist Sarah Cahill, and handful of guest instrumentalists from the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, with Kihlstedt taking center stage.

None of those resources go to waste. Amy gets a vertiginous instrumental swoosh for her fatal staircase tumble. There’s a torchy waltz for Clara, who wasted away, and a brassy neo-Bessie Smith number for the barroom brawl that leads to Prue’s decease. One of the kids (my notes on this one are useless) exults in a celebratory song reminiscent of Ives before meeting his doom abruptly. And if you want to know the sound of a child swallowing a lethal helping of tacks, Kihlstedt’s plinky percussion writing has you covered.

I confess I was skeptical of the project going in. The point of Gorey’s opus, I thought (and still think), is its suave lack of detail. Each vignette is, as the saying goes, presented without comment. Once a child has been embedded in ice, what more is there to say?

But Kihlstedt dares to ask the forbidden questions that go against Gorey’s premise. How did this happen? Why did this happen? What was the experience like for the child? The answers she comes up with are nothing short of thrilling. The tale of George, smothered under a rug, is of a game of hide-and-seek gone amiss. Zillah’s gin-soaked end turns out to be the result of a doll’s tea party using the wrong beverage. Gorey tells us that James drank lye “by mistake,” but Kihlstedt corrects the historical record by reconstructing James’s unsuccessful struggle to resist that potion’s siren call.

The cycle’s single most subversive and beautiful episode is devoted to Maud, who was swept out to sea. In Kihlstedt’s telling, this becomes an exhilarating adventure, with the protagonist depicted as hero rather than victim. “I’m standing on water!” Maud cries in an exultantly soaring melody. “I’m buoyant and free!” Death has rarely seemed so welcoming.

Elsewhere:

Lisa Hirsch, SFCV: “The composer’s wit extends to the musical settings, which encompass a vast number of vernacular styles from the last 150 years: a waltz, the blues, ragtime, something resembling a Scottish folk song, American big-band music, a ballad, 1920s Broadway, and more. The arrangements are just as clever and varied, using all manner of instrumental combinations and techniques.”

The long and the short of it

How long should a piece of music be? Obviously, there is no right answer to this question, other than the tautological “as long as it needs to be, neither more nor less.” But the Goldilocks framework of too long/too short/just right kept popping up during that performance and on subsequent evenings as well.

26 Little Deaths runs roughly an hour, give or take. Kahane introduced the performance by likening it to a nonstop flight from San Francisco to Sydney — a weird and slightly insulting simile. Many in the audience have happily sat through pieces of music considerably longer, and all of us have enjoyed movies of more than twice that runtime without complaint. In my opinion, there was no reason to pause the proceedings at all, let alone to do it several times so that Kihlstedt could make weak jokes about coming through the cabin with peanuts and towelettes.

On Friday, the third and final night of PIVOT was devoted to Seven Pillars, an 11-movement marathon by composer Andy Akiho for the quartet Sandbox Percussion. On this occasion, there were no apologies for the work’s duration. Akiho is a wondrously inventive composer, and there were boisterous delights to be had from a performance that also included staging and lighting design by Michael Joseph McQuilken. But Seven Pillars goes on at considerable length, without enough variation to quite reward the listener’s effort. When I made an early exit at about the 45-minute mark, I felt I’d heard everything the piece was likely to offer.

I left so I could head down Franklin St. for the first offering of the season from SoundBox, the San Francisco Symphony’s experimental series and performance venue. The program, curated and hosted by the pianist and composer Courtney Bryan, was designed as a tasting menu of music by composers of the global African diaspora.

I loved hearing explosive rhythmic piano etudes by Tania León and Marcos Balter, as well as a genteel excerpt from a sonatina by Roger Dickerson, all superbly rendered by pianist John Wilson. But a parade of tiny musical excerpts, only two of them lasting more than five minutes, vanished almost instantly from the memory. None of these pieces stuck around long enough to make more than a glancing impression. Goldilocks would have had some thoughts.

Elsewhere:

Lisa Hirsch, SFCV: “Seven Pillars is so complex that it’s nearly impossible to track everything that’s happening, even within a short section of the work.

Rebecca Wishnia, SFCV: “Within the context of no context, it was the longer pieces — including [George] Lewis’s bewildering one — that left the deepest impressions.”

Seniority in the workplace

Herbert Blomstedt, the former music director of the San Francisco Symphony, returned to Davies Symphony Hall on Thursday to conduct the orchestra in symphonies by Schubert and Brahms. Blomstedt is now 97 years old, and remains a powerful musical authority on the podium.

Go ahead and read that last sentence — which contains no typos — once again. I can wait.

Blomstedt now appears more physically frail than he did even during his last visit, two years ago. He walked slowly to the podium, on the arm of concertmaster Alexander Barantschik, and conducted while seated on a piano bench, as before. His conducting style is now even less physical than ever, which makes it all the more remarkable to hear what he can achieve with just a nod of his head and a flick of his fingers.

As always, there were no surprises in Blomstedt’s performances — unlike his successor Michael Tilson Thomas, he’s never been a big believer in exploring the question of What happens if we try it this way? Rather, he keeps an eye on the ideal embodiment of a given score, in an attempt to approach that model as precisely and accurately as possible.

On this occasion, that meant a homey, intimate rendition of Schubert’s Fifth, full of nuance but perhaps not much dynamic impact. Brahms’ First, by contrast, rose to its full stature, from the majestic bars of the opening through the expansive finale, in which Brahms wrestles the imposing ghost of Beethoven to something approaching a draw. That last movement, I thought, showed Blomstedt at his finest, explicating the psychological currents of the music in a way that might have been lost on a younger and less experienced conductor — which is to say, all of them.

Elsewhere:

Steven Winn, San Francisco Chronicle/SFCV: “That eventful last movement of the Brahms saw the conductor enacting his deeply considered, almost architectural approach.”

Stephen Smoliar, The Rehearsal Studio: “…even with his body language limited by his age, Blomstedt knew how to maintain the attention of the serious listener.”

Operas ahead

One of the many downsides of getting to be my age is that the way things were years ago still feels like the default. When I first began covering the San Francisco Opera, the company used to present 10 operas each season. That kind of schedule has not been seen for many years now, yet when the details of the 2025-26 season were announced yesterday — with six operas spread across the fall and summer — my first thought was “OK, but where’s the rest of it?”

Being slow to adjust to changing circumstances is, of course, my problem. The truth is that this is the kind of traffic San Francisco Opera can now sustain, and given that premise, the new season looks pretty good. It includes the commissioned world premiere of The Monkey King, a treatment by composer Huang Ruo and librettist David Henry Hwang of a classic Ming Dynasty novel, alongside a 25th-anniversary revival of Jake Heggie’s Dead Man Walking, which is arguably the most successful commission in the company’s history. Music director Eun Sun Kim takes the spotlight to conduct Rigoletto, Parsifal, and Elektra, an impressive troika.

Here are a few other aspects of the season I’m particularly looking forward to: The return of the Mongolian baritone Amartuvshin Enkhbat, who made an incendiary debut last fall in Un Ballo in Maschera, to sing the title role in Rigoletto; the new production of Parsifal, directed by Matthew Ozawa and featuring the superb Brandon Jovanovich in the title role; and the revival of Keith Warner’s visionary Elektra production, with debuting soprano Elena Pankratova in the title role and former Adler Fellow Elza van den Heever as Chrysothemis. The full season details can be found here.

Elsewhere:

Lisa Hirsch, San Francisco Chronicle: “The San Francisco Opera has again scheduled pared-down offerings for its 2025-26 season, citing the ongoing challenges in the post-pandemic world that plague the company and other arts institutions.”

Janos Gereben, SFCV: “[General director Matthew] Shilvock saw the company through serious pre-pandemic fiscal problems and then the devastation of COVID-19. The challenges show no sign of abating, but Shilvock, as usual, is positive and optimistic.”

Cryptic clue of the week

From Out of Left Field #253 by Henri Picciotto and me, sent to subscribers last Thursday:

Identify site of 1960s conflict: capital of Egypt (4)

Last week’s clue:

Coco gets adult rating, being full of dead bodies (7)

Solution: CHARNEL

Coco: CHANEL

gets: going around

adult rating: R

full of dead bodies: definition

Coming up

Marc-André Hamelin: Few pianists these days exemplify the venerable old model of composer-virtuoso like Hamelin, whose all-encompassing stylistic range is as remarkable as his keyboard technique. His recital for San Francisco Performances doesn’t include any of his own work, but it offers music by the modernist Stefan Wolpe, the still too rarely heard Nikolai Medtner, and Frank Zappa. Feb. 8, Herbst Theatre. www.sfperformances.org.

Berkeley Symphony: Dance and music have been lifelong friends, but you sometimes have to look a bit to find music that explicitly acknowledges the connection. Music director Joseph Young has done just that to program the Berkeley Symphony’s upcoming concert, which includes John Adams’ The Chairman Dances alongside DANCE, a piece by British composer Anna Clyne that features cellist Inbal Segev and the Berkeley Ballet. Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony, which Wagner famously called “the apotheosis of the dance,” completes the program. Feb. 9, Berkeley Community Theater. www.berkeleysymphony.org.

Thank you for writing such an admiring and attentive review of Carla's work. I think she is a true original, and hope that this piece will travel. At the risk of breaking the cardinal rule: I take your point about the "SFO-SYD" remark — and/but I want to add that for me, the question is not one of the audience's attention span, but the degree to which we conceive of a concert as a social encounter. I respect the Western classical tradition of silent reverence, but I think it all too often slides into self-regard, and toward a disconnect from the essential social act that is music-making and music-sharing. This may be a matter of taste — you're absolutely right that 26LD needs no interruption — but I don't think that engaging with an audience verbally in the middle of a large work need be perceived as dumbing down or hand-holding — it's an acknowledgement that we're all in the same space, breathing the same air, etc. Anyhow — thank you for coming, and for engaging so deeply and thoughtfully with Carla's brilliant work.

This piece sounds like a lot of fun, and, in its dry humor, whimsy, and pastiche, kind of reminiscent of The Magnetic Fields... extra-long Eros/Thanatos double feature of "69 Love Songs" and "26 Little Deaths," anybody?