The tao of Steve

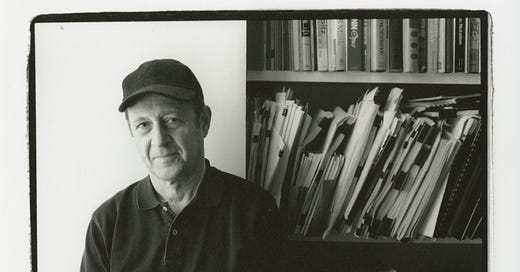

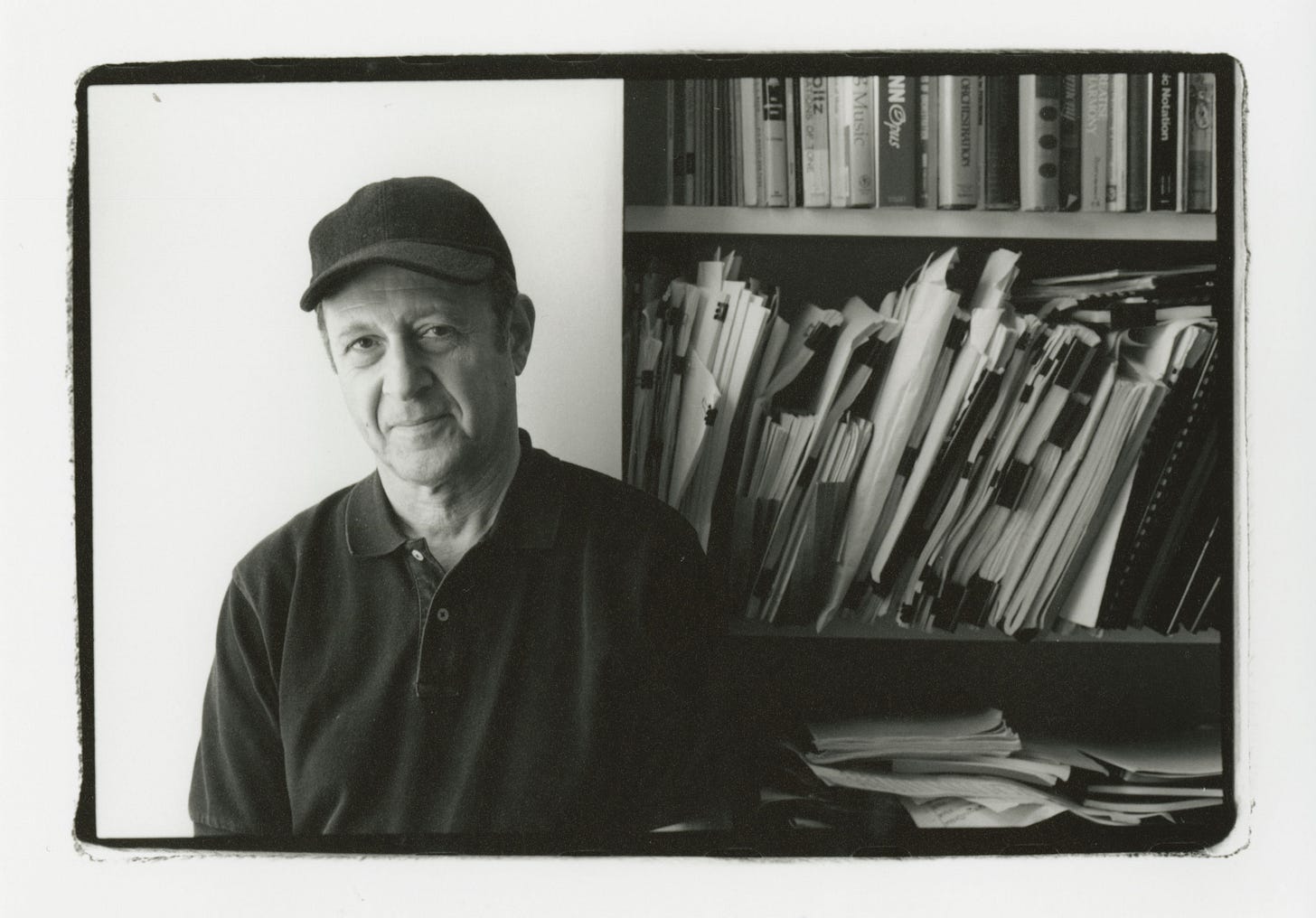

A new box set celebrates the compelling and consistent legacy of composer Steve Reich

Isaiah Berlin’s typology of artists and thinkers as either hedgehogs or foxes (“The fox knows many things, the hedgehog one big thing”) is something of a cliché by now, but that’s partly because it’s so useful. There are foxy composers — Mozart, Stravinsky, Britten — who eagerly turn their hand to whatever fresh ideas and techniques present themselves, while the hedgehogs patiently work away on whatever it is that animates their entire body of work.

Steve Reich is in the latter camp. Everything he’s written, going back to the first tape loop pieces of the 1960s, explores and expands upon a small pool of fundamental musical building blocks. Rhythm plays a central role in his music, whether as a steady pulsing backdrop or an expressive resource in its own right. He’s an inveterate weaver, stitching together musical tapestries out of melodic counterpoint and repetitions that go in and out of phase. He tends toward simple modal harmonies, which he flavors with a distinctive splash of extra notes. All those elements have been there since the beginning, and although he’s added other musical and thematic accents over the years — celebrations of bebop and Notre Dame polyphony, a focus on Jewish liturgical traditions, evocations of urban life — the core attributes of his sound remain astonishingly consistent.

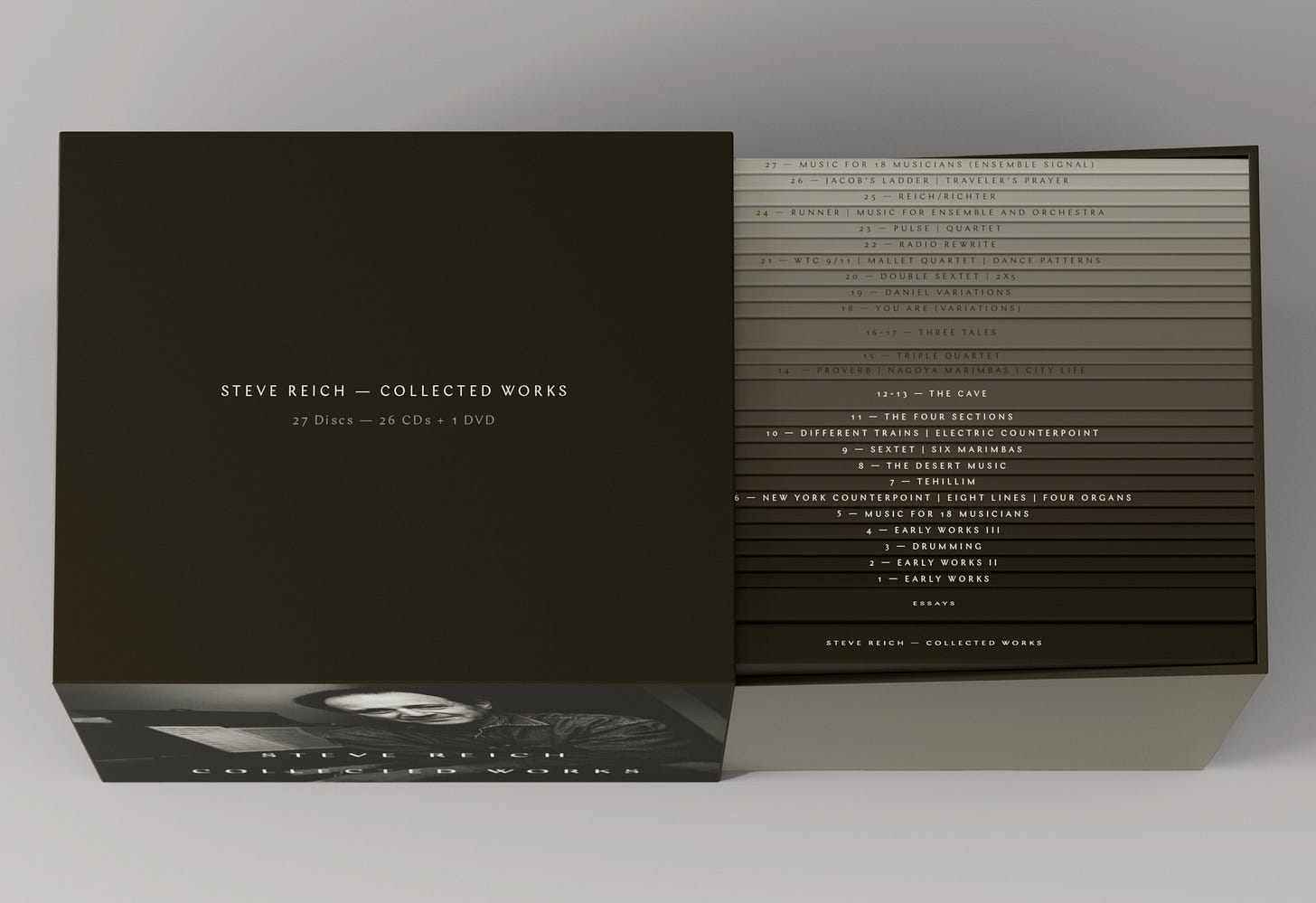

It's one thing to know this in the abstract, and another to hear and experience it through an immersion in Steve Reich: Collected Works, a massive and magnificent box set released this month by Nonesuch. Over 27 discs that cover a period of 60 years, you can witness the creative arc by which Reich found his niche early, then spent decades refining his ideas to a blinding sheen. Everything here has its roots in what’s come before. Each piece is an elaboration or offshoot — sometimes tentative, sometimes boldly triumphant — of its predecessors.

Another way of saying this is that Reich’s music all sounds fundamentally the same — except that, just as with his coeval and rival Philip Glass, one wants to frame this in a non-derogatory way. Rather, you can marvel at the incremental advances Reich makes over the years, and exult when he hits one of those breakthroughs that occur only a handful of times in any artist’s life. Music for 18 Musicians, in particular, remains the Everest of Reich’s catalog, a towering monument of expressivity and wit and joy and sensual beauty that all by itself would suffice to place him among the great composers of the 20th and 21st centuries. But of course there are many other delights here as well: the percussion extravaganza Drumming, the Holocaust memorial Different Trains, the Pulitzer Prize-winning Double Sextet, and the recent orchestral work Music for Ensemble and Orchestra, to name just a few.

And listening to Reich’s corpus in its entirety is, in a fascinating and unpredictable way, a bit like listening to just one of his pieces on a large, fractal scale. You begin by thinking “OK Steve, this is cool but haven’t we been here before? How many repetitions of this material will be enough?” Then you listen further and you realize that this is new and that is different and something’s going on in the interstices that casts things in a wholly unexpected light. And you suddenly understand that what’s really needed is more repetitions, and you go back and play the thing again.

A new Leif

The wonderful Norwegian pianist Leif Ove Andsnes has been a fixture of the music pantheon for so long — both internationally and as a frequent visitor to the Bay Area — that I did the unforgiveable and began to take him for granted. When offered the opportunity to commune with a performing artist of such lithe virtuosity and expressive grandeur, surely only a fool says, “Thanks, but I know all about that.” (It’s me, I’m the fool.) Tuesday night’s potent recital in Zellerbach Hall, presented by Cal Performances, was the first time I’d heard him perform in a number of years, and it was both a thrill and a reproach.

My comeuppance was swift, as Andsnes launched into a handsomely chiseled account of Grieg’s Piano Sonata, followed after intermission by a compelling romp through the Op. 28 Preludes of Chopin. But the proximate cause that got me to Berkeley on this occasion was Andsnes’ plan to perform a piano sonata by the Norwegian composer Geirr Tveitt, whose name was unknown to me. Chasing after novelty turned out to be a winning strategy: Tveitt’s Piano Sonata No. 29, which he premiered in 1947, was a revelation, a big, compelling craggy monster full of beguiling melody, virtuoso keyboard work and inventive piano effects. I was enraptured.

Tveitt, who died in 1981 at 73, is evidently well known in his homeland as a collector and arranger of folk music. But this sonata, although it includes a pair of Norwegian folk melodies as thematic material, finds him operating in the late Romantic vein of the composer-pianist. Over three movements spanning half an hour, he creates great thunderous flurries of sound alternating with tenderly rhapsodic passages. At a few important junctures he has the performer silently depress the lower keys, lifting the dampers so that the strings ring out in response to percussive single notes — a hypnotic effect. The finale is a furious and dazzling exercise in perpetual motion, which Andsnes maintained in perfect form without breaking a sweat.

Want to hear more of Tveitt’s music? So do I. Alas, we’re out of luck. In 1970, his rustic home in the Hardanger district burned to the ground, destroying most of his voluminous musical output. According to Andsnes, the Sonata No. 29 was the only one of 30 piano sonatas to survive the conflagration.

Elsewhere:

Lisa Hirsch, Iron Tongue of Midnight: “The Tveitt sonata has its moments, particularly in the last of the three movements, and Andsnes made the most of them, particularly the dramatic ending. The first movement has a lot of what I would call obsessive — but not very interesting — repetition in the right hand, with countermelodies in the left.”

From ear to ear

Find someone who looks at you the way Gil Shaham looks at his violin — as if you’re the most wondrous and enchanting creature they’ve ever seen.

Shaham, who came to Davies Symphony Hall on Thursday to play the Brahms Violin Concerto with the San Francisco Symphony and guest conductor Juraj Valčuha, plays with a combination of vigor and silky elegance that is always rewarding. But what I like best about his performances is how goddam happy he always is to be there. He starts grinning when the first note sounds, and doesn’t let up until the applause starts. He persuades you that just being there, playing or listening to Brahms, is one of life’s great privileges, and it’s hard to disbelieve him — even when it takes him the first movement and a quick, much-needed retuning to really find his footing.

The second half of the program was devoted to Shostakovich’s Tenth Symphony, which was the third outing for the piece in Davies in the past eight years. That’s at least two too many — three if you’re as cranky about Shostakovich as I am — and although I admired Valčuha’s ability to muster and shape large masses of orchestral sound, I found it hard to care all that much. Perhaps the evening’s most exciting development was another chance to hear Joshua Elmore, the orchestra’s new principal bassoonist, in action. Shostakovich gives him two prominent solos, one in the first movement and another in the finale, and he rose to the occasion both times. Elmore has a wonderfully arresting sound, tender and fluid and with lots of presence; there’s a lot going on in every measure he plays. Whatever else may be happening in Davies, the orchestra itself just keeps sounding better and better.

Elsewhere:

Rebecca Wishnia, San Francisco Chronicle/SFCV: “[Shaham’s] playing was breathless and rhythmically frank, the runs free and easy. He became animated in his responses to the orchestral musicians — even when he was at rest, as in the second movement adagio, whose simple song principal oboe Eugene Izotov played with utmost sweetness.”

Cryptic clue of the week

From Out of Left Field #261 by Henri Picciotto and me, sent to subscribers last Thursday:

Fruit liqueur, at first, is bluish gray (5)

Last week’s clue:

Honors damsel in distress (6)

Solution: MEDALS

Honors: definition

damsel: anagram fodder (letters to be anagrammed)

in distress: anagram indicator

Coming up

• Elliott Sharp: The prolific New York composer and guitarist Elliott Sharp is one of those musical figures who can dissolve genre boundaries through sheer force of will. His work shares something with experimental music, classical composition, free jazz, electronica and more, without ever quite being beholden to any of it. He comes to San Francisco for two dates, a solo show followed by a collaboration with pianist Brett Carson and percussionist Jordan Glenn. April 3-4, Center for New Music. www.centerfornewmusic.com.

• 21V: The new choral ensemble, composed of soprano and alto singers of all genders under the leadership of conductor Martin Benvenuto, presents a program with a focus on the possibilities and dangers of advanced technology (among others). Titled “Promise & Peril,” the program includes world premieres by Eric Tuan, Karen Siegel, and Juan Stafforini. April 4, Old First Church. April 5, Berkeley Hillside Club. www.21vchoir.org.

• New Century Chamber Orchestra: The Korean-born San Francisco composer Jungyoon Wie explores the implications of the immigrant experience in A Prayer for Peace, co-commissioned by the New Century Chamber Orchestra and the Boston chamber orchestra A Far Cry. For the work’s first local performances, music director Daniel Hope has paired it with music by Adolphus Hailstork and Richard Strauss. April 4-6, Berkeley, San Francisco, and Tiburon. www.ncco.org.

I hope that every music school in the country is a subscriber to this substack and recommends it to their students. Your analysis of composition, musicianship, and performance skills is inspirational and a lesson for us all--thanks for the great reads.

I read this right after seeing the New Century Chamber Orchestra perform live on John Mulaney's Netflix show! When's the last time a talk show host booked a classical music performance?