Music in a time of war

The Israel Philharmonic’s visit raised perennial questions about art and politics

On Sunday night, just days after a renewed Israeli military assault on Gaza killed hundreds of Palestinians in contravention of a putative ceasefire, the Israel Philharmonic made a touring visit to Davies Symphony Hall under the auspices of the San Francisco Symphony. The timing wasn’t great, but on the other hand I don’t know that another date would have been any better.

Over the past year and a half, we’ve watched in horror as an increasingly authoritarian Israeli government has unleashed the full fury of its formidable military on the population of Gaza — slaughtering tens of thousands of Palestinian residents and displacing millions, targeting hospitals, schools, and journalists, and turning a dense population center into a wilderness of rubble so far-reaching that only Jared Kushner’s ghoulish plans for an apartheid beachfront resort could ever make it inhabitable again in our lifetime.

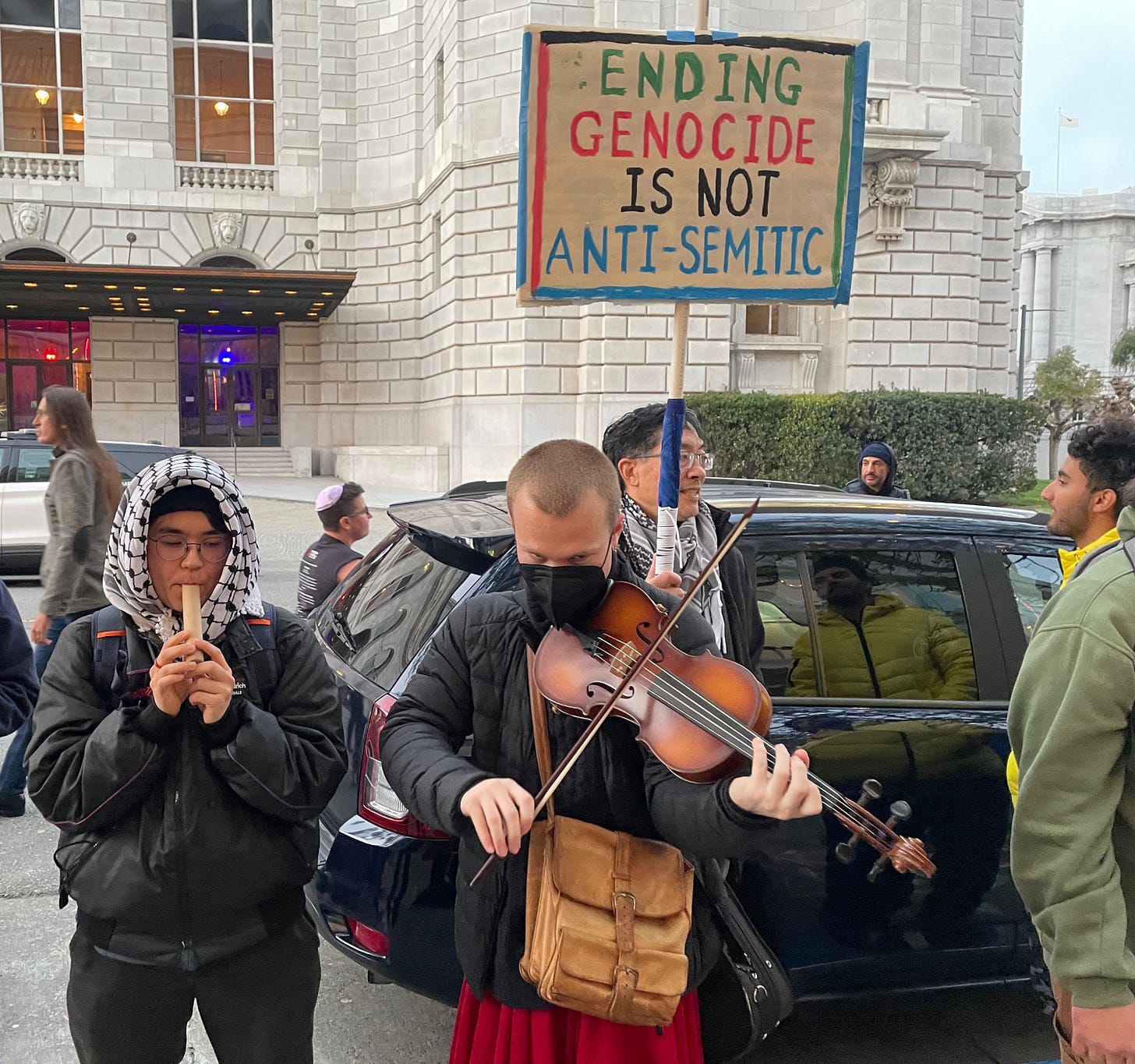

So when the Israel Philharmonic arrived in San Francisco, I had a choice to make. I could attend the concert, cheerfully soaking up the music of Bernstein and Tchaikovsky while pretending that the atrocities taking place on the other side of the world were none of my concern — or worse yet, that they were taking place with my implicit approval. Or I could stand outside Davies, raising my voice along with others in opposition to the Israeli government and its crimes.

It wasn’t a difficult call.

Now, one might object (forgive me, ingrained habits of Talmudic disputation can be hard to shake off) that a visit by a group of orchestral musicians has only a tangential relationship to the geopolitical and military situation. These are violinists and oboists, not drone pilots or intelligence officers. Can there be no safe space, no carved-out terrain where music exists to gladden our hearts without the intrusion of politics writ large?

The short answer is no. Of all the things the late Berkeley musicologist Richard Taruskin taught us, probably the most important and timeless is that art never exists in a vacuum. Music as a cultural activity is inextricably enmeshed with everything else human beings do, including economic systems and political systems and the structures of power that allow some societies to brutally impose their will on other societies.

This would be true under any circumstances, but it’s doubly true in the case of the Israel Philharmonic, which has never pretended to be anything but an instrument of nationalist propaganda. When the orchestra tours in the U.S. — and this is the only orchestra I can ever remember doing so — it performs on a stage flanked by the Israeli and American flags, and begins its concerts by performing the national anthems of both countries. Every concert is both a musical event and a claim to political allegiance; you can’t have one without the other.

The confluence of music and politics is in fact a venerable tradition, offering tools that can be wielded in a variety of ways. Readers of a certain age may remember the Sun City boycott of the 1980s, when performing musicians (some of them, anyway) refused to perform at the South African luxury resort to protest that nation’s system of apartheid.

Similar boycotts are now being levied against the U.S. in reaction to the horrific excesses of the Trump regime. Just this past Friday, the German violinist Christian Tetzlaff was scheduled to appear with his eponymous string quartet at Herbst Theatre under the auspices of San Francisco Performances. But in February, he cancelled all his U.S. appearances. “I pay 32 percent taxes on every concert I play in the United States,” he told the New York Times’ Javier C. Hernández. “That goes, at the moment, to a state that does partially horrible things with the money.”

Then a week ago, on March 19, the Hungarian-born pianist András Schiff made a similar pronouncement, pulling out of all his scheduled U.S. dates. “We do not live in an ivory tower where the arts are untouched by society,” he said in a public statement. “Arts and politics, arts and society are inseparable.”

Both of these artists understand quite clearly that there is a dark and terrifying tide rolling over the polities of the world — not just in the U.S., but across Europe and South America and the Middle East — and that it’s incumbent on every one of us to resist those forces in whatever way we can.

I’m well aware of the reaction this column will elicit, especially from my fellow Jews: You should be ashamed. (I heard these words more than once outside Davies.) And to that, my response is: Of course I’m ashamed. How could I not be ashamed?

I’m ashamed that so many Jews have evidently abandoned the fundamental moral strictures we all had instilled in us as children — strictures against murder and cruelty and injustice — and chosen to operate instead out of fear or xenophobia or simple bloodlust. I’m ashamed that my country — which, lest there be any doubt, is the United States and not Israel — has rushed so eagerly to help with money and munitions to perpetrate crimes on a massive scale.

The only thing that could make me any more ashamed than I am, as an American and a Jew, would be to keep silent about it.

Cryptic clue of the week

From Out of Left Field #260 by Henri Picciotto and me, sent to subscribers last Thursday:

Honors damsel in distress (6)

Last week’s clue:

Minor star appears in World War Five (5)

Solution: DWARF

Minor star: definition

appears in: hidden in the letters of

worlD WAR Five

Coming up

• Oakland Symphony: Among the most productive partnerships the musical world can offer is one between an orchestra and a composer, since the latter can’t always be sure how their work is landing until they actually hear it in performance. This week marks the beginning of such a partnership between the Oakland Symphony and composer Daniel Bernard Roumain, who plans to create a newly commissioned piece for a 2026 premiere. For now, music director Kedrick Armstrong will conduct “Forgiveness,” a work for spoken words and orchestra by Roumain and writer/performer Marc Bamuthi Joseph, along with music by Gabriela Lena Frank and Mussorgsky/Ravel. March 28, Paramount Theatre, Oakland. www.oaklandsymphony.org.

• Voices of Silicon Valley: The innovative French composer Gérard Grisey, who died far too young in 1998, at 52, wrote music whose transformative, radiant sonorities are still being discovered by contemporary audiences. Voices of Silicon Valley, led by Cyril Deaconoff, will give the U.S. premiere of his “Songs of Love,” alongside a world premiere by UC Berkeley composer Edmund Campion and Fauré’s Requiem. March 29, Grace Cathedral. www.voices-sv.org.

Thank you, I think this is an important statement.

Thank you for your courage. You are absolutely right, of course. I remember that Casals when asked about his ethical and political stance and it’s relevance to his art replied that he was a human being first and a musician second. As a US citizen and the son of a Holocaust survivor I am deeply ashamed of Israel’s actions, so strongly backed by the US , which claim to be in my name.