Poetic justice

Kevin Puts' new song cycle shone a beautiful light on Emily Dickinson's poems

One of the great things about Emily Dickinson’s poetry, as I understand it, is the capacious range of the work — its full-heartedness, its variety, the way it seems to expand under our gaze like so many flowers opening to the sun. The poems seem small and constricted on the page, but turn out in the right light to have far-reaching expressivity. This, as I say, is my best guess; I speak as one who has repeatedly tried, without success, to appreciate (let alone love) Dickinson’s poetry. That’s a wholly personal failing, of course, which I would no more try to argue for or defend than I would my inability to eat mushrooms. But it does mean that I’m open to being won over.

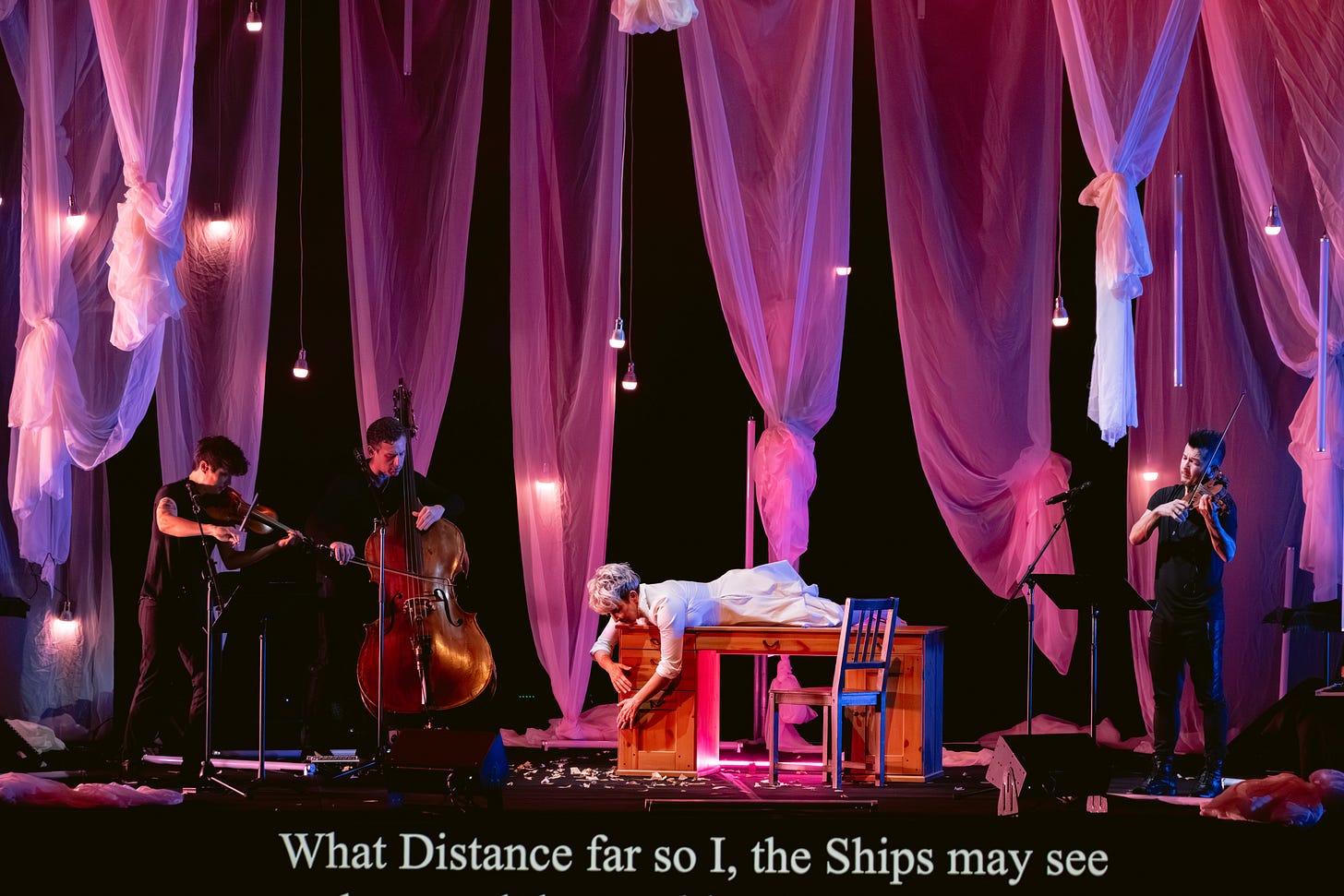

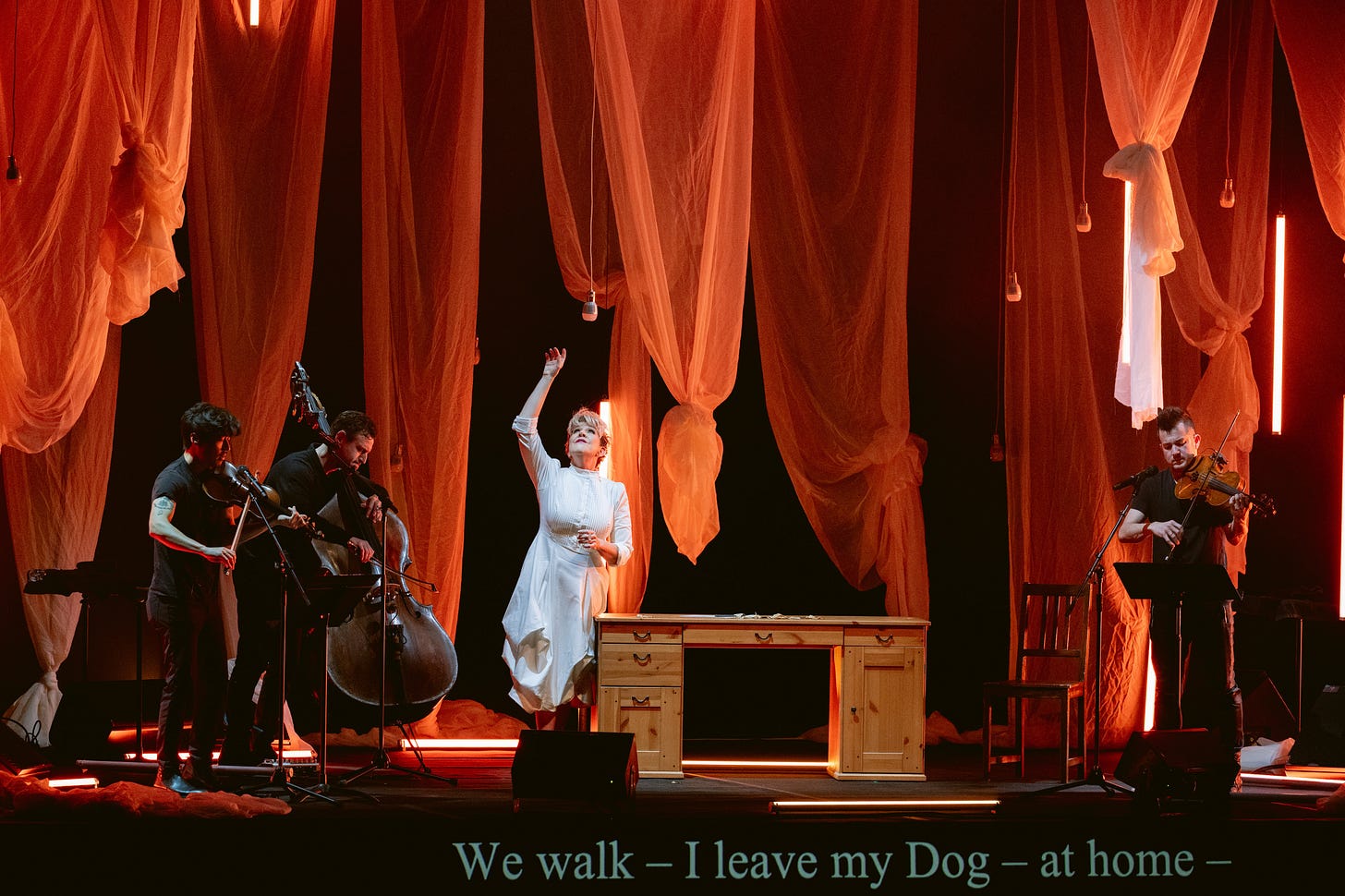

I came as close as I’ve ever come on Saturday night, when mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato and the instrumental ensemble Time for Three came to Zellerbach Hall, under the aegis of Cal Performances, to perform Kevin Puts’ magnificent song cycle Emily — No Prisoner Be. The title is syntactically rockier than one might wish, but it’s easy to overlook that misdemeanor given music of such versatility, interpretive insight and sheer sonic beauty. There were times during the elaborately staged performance when I could barely believe the richness of what I was hearing. There were passages that illuminated a line or even an entire poem of Dickinson’s in ways I would not have thought possible. The performers were endlessly responsive and alert to the score’s demands. The evening was little short of breathtaking.

Puts’ cycle runs about 80 minutes and includes settings of some two dozen poems, give or take. (A few poems aren’t sung, but serve as inspiration for a wordless instrumental interlude.) What’s initially most striking is the piece’s stylistic range, which includes among other things abstract modernism, bluegrass, choral textures, and much more. With each new song, it’s as if Puts had swept everything off his writing desk — every assumption, every harmonic and rhythmic template — and set out to create from scratch. Among the piece’s many highlights, I would particularly call out Puts’ gentle, spare setting of “I was the slightest in the House,” the rousing audience singalong for “No Prisoner Be,” the ingenious rhythms of “Because I could not stop for Death,” and above all the wordless Appalachian choral ballad that serves as a “setting” for “‘Hope’ is the thing.”

You don’t have to read Puts’ program note to guess that the piece was inspired by his previous collaborations with these specific artists. DiDonato, who had been an eloquent but reserved Virginia Woolf in Puts’ opera The Hours, turned Dickinson into a more extroverted character, as if to let us see beyond the poet’s mousy exterior to the passion within. Time for Three (violinist Charles Yang, violinist/violist Nicolas Kendall, and bassist Ranaan Meyer) are not only virtuosic string players, but vocalists as well; whenever a bit of three-part harmony suddenly appeared, it felt as though a new dimension had been added to the musical texture.

Puts’ stylistic conservatism — his preference for tonal harmonies, accessible rhythms, and frank emotion — has been irksome to some listeners of a progressive bent. I understand, and have occasionally shared, their sense of impatience. But when the subject matter calls for those tools, as in The Hours and this song cycle, he’s a master. He can unerringly press melody and texture into the service of humane and deeply expressive ends — which is just what a subject like Emily Dickinson requires.

Elsewhere:

Steven Winn, San Francisco Chronicle/SFCV: “DiDonato sang as she always does, with peerless technique, a captivatingly mobile voice, burnished amber tone and seemingly depthless resources of emotional nuance, fervor, fearless line readings, rapture, and interpretive acuity. Every syllable got full attention from her and the audience.”

The Handel whisperer

Nicolas McGegan was the music director of Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra & Chorale for 35 years, almost from the organization’s founding in 1980. He conducted the music of countless different composers over the decades, from the early Baroque masters to living creators. What remained constant throughout that period was that McGegan was a phenomenal Handel conductor — probably the best I’ve ever heard — and that his performances of Handel’s music outshone his work in that of any other composer. By a lot. There was a clarity, a vivacity, a formal brilliance to his Handel that he rarely matched, even in the music of superficially similar composers like Bach.

So when McGegan returned on Friday night to conduct the orchestra he now serves as Music Director Emeritus, the headline news was “McGegan conducts Handel!” The first half of the program was devoted to the composer’s 1707 psalm setting Dixit Dominus, and lord, it was sublime. In one movement after another — solos, choruses, small groups of vocalists — McGegan shaped the music with his characteristic blend of translucency and fleetness. There were vibrant solo contributions from soprano Nola Richardson and tenor Aaron Sheehan, and the Philharmonia Chorale, ably led by Valérie Sainte-Agathe, sounded forceful and well-blended, especially in the powerful final “Gloria.”

Still, McGegan remained the hero of at least this part of the evening. One of the things I’ve always loved about his conducting in general, and in Handel in particular, is how lightly and effortlessly he seems to get the results he wants. He gives his little downbeat, and the music takes off, with him seeming to coast like a water-skier on its surface. It’s an illusion, of course — every performance is dexterously plotted to bring out both the tonal beauty and the constructive ingenuity of the music — but it’s a joyful one.

Things don’t always go that splendidly, of course. The long second half of Friday’s program was given over to Rameau’s The Garland, or the Enchanted Flowers, an “acte de ballet” combining (in its original form) a two-character minidrama and several dance interludes. It was pretty boring. Operatic recitatives and standalone dance numbers (especially when there’s music but no dance) are among the dullest things Baroque music has to offer, and this had both of them. I don’t think the dullness was the fault of McGegan or any of the performers — I think the problem lies with Rameau and with the demands of the genre, in some proportion — but in any case no one was able to rescue the piece.

The Mozart whisperer

So was the entire week just one musical delight after another? Y’know, it kind of was. It began on Thursday in Davies Symphony Hall, when guest conductor Harry Bicket led the San Francisco Symphony in a scintillating and sturdy all-Mozart program. Mozart’s music doesn’t often fare well in the hands of a traditional standard-rep orchestra like the Symphony — not because its players aren’t virtuosos who can tear through anything that shows up on their music stands, but because Mozart requires a very specific stylistic mindset that is not part of a modern orchestra’s bedrock practice. Even Haydn is more closely connected to the orchestral tradition, because he taught Beethoven how to write a symphony, and of course Beethoven then went on to define everything that came after.

But Bicket is the longtime artistic director of the English Concert, one of the leading period-instrument ensembles, and when you put an early music specialist like this on the podium, things can begin to sparkle. Bicket understood how to give this music a lean, whippet-like physique — fast out of the gate, clearly focused on rhythmic goals — without sacrificing anything in the way of tonal resplendence. The two symphonies on the program, Nos. 34 and 38, were marvels of concision and power; the sleek finale of Symphony No. 34, in particular, was an edge-of-the-seat affair.

Topping it all off was the presence of the luminous South African Golda Schultz, who brought elegance and vigor to a trio of arias, one from each of Mozart’s collaborations with the librettist Lorenzo da Ponte. Schultz has been an all-too-rare visitor to the Bay Area (one appearance each with the Symphony and the San Francisco Opera, a couple of recitals under the auspices of San Francisco Performances). But her silvery, full-bodied tone is something to savor, and she deployed it with keen dramatic timing — especially in “Or sai chi l’onore” from Don Giovanni, for which she had keen support from tenor Samuel White, a recent Adler Fellow. It’s not too soon to start keeping an eye out for Schultz’s next appearance.

Elsewhere:

Lisa Hirsch, San Francisco Chronicle/SFCV: “The first half of the program — the Serenade in D Major, K. 238, “Serenata notturno,” and the Symphony No. 34 in C Major, K. 338 — came across as faceless and in need of more wit and spark.”

Matthew Travisano, Parterre Box: “Schultz is a solid musician, but the wispy accompaniment Mozart provides left Schultz sounding on her own. Bicket’s somewhat sluggish tempo also didn’t help.”

Michael Strickland, Civic Center: “I have heard enough deadly dull live Mozart performances over the years that it always feels like a small miracle when musicians perform him well. Bicket’s conducting style was crisp and transparent, which worked well, and the musicians seemed to be enjoying themselves immensely.”

Cryptic clue of the week

From Out of Left Field #306 by Henri Picciotto and me, sent to subscribers last Thursday:

Elevated song includes feet (6)

Last week’s clue:

Like a sex scene with Mae West in a filthy location (6)

Solution: STEAMY

Like a sex scene: definition

Mae West: EAM (MAE reading east-to-west)

in: container

filthy location: STY

Coming up

• Cavalleria Rusticana & Pagliacci: The classic double bill of verismo opera — fierce, raw, and tender — returns to Opera San José in a new production directed by the company’s general director, Shawna Lucey. Soprano Maria Natale and tenor Christopher Oglesby take the leads in Cavalleria, while the Pagliacci cast features tenor Ben Gulley, soprano Mikayla Sager, and baritone Kidon Choi. The wunderkind composer and conductor Alma Deutscher, who turns 21 shortly into the run, is set to conduct. Feb. 15-March 1, California Theatre, San Jose. www.operasj.org.

• Sacred & Profane: In honor of Valentine’s Day, the Bay Area chorus offers a program of love songs ranging from the Renaissance to the present day. Artistic and executive director Rebecca Petra Naomi Seeman leads the ensemble in music by the 16th-century English master Thomas Morley, the ever-popular Morten Lauridsen, Reena Esmail, and more. Feb. 14, St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, Berkeley. Feb. 15, Noe Valley Ministry. www.sacredprofane.org.

• Voices of Music: This well-regarded early-music ensemble is also celebrating Valentine’s Day, with music of love from the 17th and 18th centuries. Soprano Amanda Forsythe is the soloist in a program that includes works by Purcell, Corelli, John Jenkins, and more. Feb. 13, First Congregational Church of Palo Alto. Feb. 14, Old First Church. Feb. 15, First Congregational Church of Berkeley. www.voicesofmusic.org.

I went to Davóne Tines instead of JDD – I liked him a lot – but now I'm kinda wishing I'd taken the JDD review.