Prodigal daughter

Even a brief San Francisco return by composer Chen Yi was cause for celebration

In the early 1990s, for a short and wonderful period, the composer Chen Yi was a fixture on the musical landscape of the Bay Area. She had a joint residency with the Women’s Philharmonic of blessed memory and the men’s chorus Chanticleer, and once or twice a year local audiences would get to savor the products of her incredible musical imagination. Chen Yi’s work draws a lot on the traditions of her native China, but the integration of Asian and European/American models, which can often devolve into a tired trope in less gifted hands, always sounds fresh and alive with her. Her music is surprising and unpredictable, but always accessible. (At one point the Chronicle columnist Jon Carroll attended a concert of her music on my recommendation, and pronounced it “modern, but in a nice way.”)

We haven’t heard much of Chen Yi’s music around these parts in the ensuing decades, but Saturday’s engaging program by the San Francisco Contemporary Music Players brought all the happy memories rushing back. The concert, led by artistic director Eric Dudley, included offerings by a range of composers (living and not), before culminating with Fire, Chen Yi’s brief and fiercely powerful evocation of the title element. The piece, which is scored with translucent vivacity for a dozen instruments, bolts out of the gate and proceeds to consume everything it touches. Rapid bursts of melody fly upwards, only to be overtaken by a new strand from elsewhere in the ensemble. Instrumental sparks strew themselves across the stage. The experience is brilliant, vivid, and frankly just a little scary. And then, just like that, it’s over, leaving what feels like a backdraft of silence in its wake.

Fire offered the evening’s most intense delight, but not the only one. Elizabeth Ogonek, a composer who inspires ever-greater admiration with each encounter, opened the program with Lightenings, a luminous set of variations on a Byzantine hymn with inspiration from the poetry of Seamus Heaney. By turns light-footed and elegiac, each of these short movements creates a distinctive world full of beauty and grace. I also enjoyed the expansive sinew of Justin Weiss’s through depths and shadows (one day soon composers will realize what’s what and bring capital letters back to their titles, but evidently not quite yet), and the roisterous stomp of Viet Cuong’s Electric Aroma, a fast jittery tango for clarinet and soprano saxophone accompanied by piano and percussion.

Russian around

It took me far too long to grasp the simple truth about Chekhov, which is that he only makes sense on the stage. Encountered on the page, his world seems to be largely populated by dimwits, fabulists, and bumblers, spewing reams of disconnected non sequiturs about their past and their hapless dreams for the future. The humor isn’t really funny, just weird. None of the characters seem to have any sense of how normal people converse.

But all that changes as soon as a first-rate director — in this case Carey Perloff, whose exhilarating production of The Cherry Orchard opened Tuesday at the Marin Theatre — puts a piece onstage and, together with the cast, takes charge of shaping the proceedings. At that point we understand the characters themselves, and the words Chekhov places in their mouths. All the fools and strivers are still there — that wasn’t an illusion — but now everything they say lands like an authentic expression of their pain, their history, their (mostly dashed) hopes. The reason they talk like that, it turns out, is because that’s genuinely who they are. They’re only half-listening to what anyone else says because their private drama dominates their attention. They’re funny — the objects of humor, rarely the source of it — because from the audience we can clearly perceive how far every one of them falls short of their own self-conception. And yet we regard them with tenderness and love, all of them, because Chekhov teaches us how to do so.

The Cherry Orchard, a play about loss and failure and the inevitability of change, may be one of the best showcases for Chekhov’s trademark combination of generosity and mockery. There are some dozen characters caroming about the stage like billiard balls, each with their own collection of follies, regrets, and aspirations, and what makes this production soar is the crisp specificity with which all of them are delineated. You can see right into the mind of Lyubov Ranevskaya (Liz Sklar), the aristocratic landowner whose nobility and soft-headedness have combined to lead to the impending sale of the family estate. The nouveau riche Lopakhin (Lance Gardner) operates on simultaneous tracks of acquisitiveness and kindness. Anya (Anna Takayo) is an ingenue with a bit of a twist, while Trofimov (Joseph O’Malley), the perennial student and maddeningly undisciplined political thinker, floats through the proceedings with an irresistible air of vague befuddlement.

If you mentally dolly back a bit from the action, you can see that The Cherry Orchard is an extended, almost encyclopedic anatomy of Russian society at the beginning of the 20th century. But doing that means disengaging your focus from the buzzing, detailed human comedy that Perloff and the fine cast have assembled for our pleasure. Every one of them demands, and repays, our full attention.

The Cherry Orchard: Marin Theatre, through Feb. 22. www.marintheatre.org.

Elsewhere:

Lily Janiak, San Francisco Chronicle: “There’s a difference between characters not meshing and actors not meshing. As nouveau-riche neighbor Yermolái (Lance Gardner) tries to impress upon the profligate Liubóv that her property is in arrears and about to be auctioned off, the rules and tone of their world still seem unsettled under the direction of Carey Perloff.”

Steve Murray, Broadway World: “Watching Chekhov’s Cherry Orchard, brilliantly directed by… Carey Perloff and starring an all-star cast of local legends, will make you jump into action. The characters presented here are so stultifyingly stuck in their past that you want to slap them upside the head and scream ‘wake up.’”

Caroline Crawford, Bay City News: “Marin Theatre’s new, high-spirited production of Anton Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard has a first-rate cast and stage design that detail in full color the decline of the Russian aristocracy as it was in the early 1900s before the revolution.”

True grid

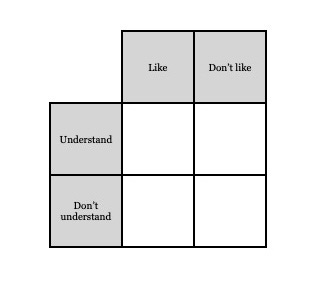

At the most reductive level, one’s reactions to a new piece of music (or any artwork, I suppose) can be mapped onto a rudimentary 2x2 matrix, with axes labeled “like/don’t like” and “understand/don’t understand.” With a little nudging, you can locate just about any musical experience within one of the four resulting pigeonholes.

The simplest and most elementally gratifying slot is in the northwest corner, where an artist does something you basically grasp and basically appreciate. The southeast corner is less pleasant but just as simple conceptually: I get what the composer was going for here, and here’s why I don’t think it worked. The magical slot is in the southwest, the natural habitat of pieces that are exciting or surprising or beautiful or all of the above, but for reasons that you just can’t put your finger on.

For a critical listener, those three are relatively easy to handle; it’s the remaining berth that’s the nightmare. Those are the pieces that make you think Well that was no fun. Also, though, I have no idea what the composer was trying to do. It’s hard to honestly critique a piece of music when you don’t like how it sounds and also don’t know why it sounds that way. Where do you even begin? There are composers whose work I stopped reviewing because it always seemed to wind up under this rubric.

I thought about this corner of the matrix on Friday night, during the opening concert of the Pivot Festival, San Francisco Performances’ annual festival of new and experimental music. This year’s series was curated by percussionist Andy Meyerson, who together with guitarist Travis Andrews makes up the excellent new-music duo The Living Earth Show. According to Meyerson’s spoken remarks, the three-night schedule was intended as a guide to his cohort of musical colleagues, those in their mid-40s give or take.

Friday’s opener, titled Legacies, was devoted to the six members of the Sleeping Giant composers’ collective, a group that includes such prominent figures as Andrew Norman, Ted Hearne, and Timo Andres. Each of them was represented alongside one of his students, creating a 90-minute flow of a dozen vocal works (sung by Tanner Porter) that showcased two generations of creative voices.

I so much wanted to exult in this cornucopia of new and recent work, but it was all intended for other listening sensibilities than mine. The textures struck me as overbearing and dense, the harmonic language as opaque. The influence of pop music was often in evidence, but rarely in a convincing way. The one selection that truly spoke to me was the most out of sync with the others: “Through,” a limpid and lovely folk-rock ballad by Akshaya Avril Tucker, adorned by a melody that turned big intervallic leaps into sheer poetry.

Elsewhere:

George Papajohn, SFCV: “The performance closely resembled that of an eclectic and hyper-literate indie rock band. Beyond the art pop instrumentation and professional visual production, the energetic onstage activities did not align with classical conventions.”

Cryptic clue of the week

From Out of Left Field #305 by Henri Picciotto and me, sent to subscribers last Thursday:

Like a sex scene with Mae West in a filthy location (6)

Last week’s clue:

Quiet afterthought involving border crustaceans (7)

Solution: SHRIMPS

Quiet: SH

afterthought: PS

involving: going around

border: RIM

crustaceans: definition

Coming up

• SoundBox: The latest installment of the San Francisco Symphony’s experimental music series has been curated by violinist Alexi Kinney — in his early days the concertmaster of the Symphony Youth Orchestra and now a virtuoso of expansive musical interests. What he’s come up with for this program is still being kept under wraps for some reason, but it’s sure to be interesting. Feb. 6-7, SoundBox. www.sfsymphony.org.

• Davóne Tines: The brilliant and charismatic bass-baritone is joined by the instrumental ensemble Ruckus for an eclectic recital ranging from Handel to Sam Cooke. Music by Douglas Adam August Balliett, Julius Eastman, Stephen Foster and more populates the program. Feb. 7, Herbst Theatre. www.sfperformances.org.