Screen idol

As Chronicle film critic Mick LaSalle steps down, a four-star review of his brilliant career

Over the years I’ve developed a central maxim about arts criticism, which is that it’s really just the answer to the question “So what’d you think?” I lean heavily on this formulation when teaching, and in other circumstances as well, because “what’d you think?” is a question all of us routinely ask and answer. The point is to try to demystify a practice that many people regard as rarefied or arcane, but that I believe is as natural and intuitive as singing, dancing, or banging on cans. Writing music or film or dance criticism is a formalized version of something everyone does all the time.

There are very few critics who take the business of “So what’d you think?” more seriously than Mick LaSalle, the longtime movie reviewer for the San Francisco Chronicle who retires this month after nearly 40 years at the paper. Readers, very much including me, have learned to rely on LaSalle for deeply perceptive responses to just about everything that lands on local movie screens, from arty French dramas to crowd-pleasing American schlock. And although I understand his desire to move on — to leave behind the daily grind of reviewing, to focus on other kinds of writing, to go to zero more staff meetings — his retirement will leave a cavernous hole where his coverage used to be. (Fortunately, he plans to keep contributing reviews to the paper on a freelance basis.)

I have some thoughts about the virtues that have made him such a terrific critic.

Probably the most obvious one is the unadorned vigor with which he buckles down to his task. Open one of LaSalle’s reviews and you immediately get hit with an answer to the question, “Was this picture any good?” By necessity, that answer is rarely simple (although LaSalle knows more subtly different categories of “the movie stinks” than indigenous Arctic dwellers know for snow). But he tackles it immediately and energetically. There’s no throat-clearing and no philosophizing, except when it will help situate the movie under discussion. LaSalle understands that the reader is waiting for a verdict, and that the clock is ticking.

On top of that briskness is a prose style as naturalistic and conversational as anyone’s in the business. Not even the great Roger Ebert ever mastered the illusion of we’re just shooting the shit here, you and I the way LaSalle can. It’s not even an illusion, really — if you ever hear LaSalle talk about the movies, you’ll hear the exact same voice you hear in his writing. The only difference is the paragraph breaks.

Watch him leap into action in these opening paragraphs, chosen almost at random from the big database of his reviews that LaSalle and the Chronicle assembled to mark his retirement.

• In Oppenheimer, Christopher Nolan takes an eggheady topic and, without insulting anyone’s intelligence, turns it into a gut-level experience. He shows that the kind of hyper, jacked-up, ultramodern filmmaking associated with the action and superhero genres can be harnessed in the service of a smart, serious movie.

• Saltburn is a remarkable combination of smart and stupid. Its problem is that it’s superficially smart and deeply stupid. It’s clever and amusing in 20 different ways, but when it really matters, it descends into ridiculousness.

• Don’t Look Up might be the funniest movie of 2021. It’s the most depressing too, and that odd combination makes for a one-of-a-kind experience. Writer-director Adam McKay gives you over two hours of laughs while convincing you that the world is coming to an end.

Also, the guy is funny as hell. I’ve been chuckling to myself over this opener for more than a decade now:

Nobody wants Robert Redford to drown, but to really care about All Is Lost, the fear of Redford drowning must practically be an ongoing issue in your life. It can't just be something you develop over the course of the movie. No, you really need to have been worrying about this for years.

But the best aspect of LaSalle’s work, the thing that puts him in a class of his own to my mind, is this: His reviews contain a lower proportion of plot synopsis to analysis than those of any film critic I know.

Anyone who’s ever had a five-year-old tell them about a favorite movie knows that it goes something like this: “The lions have a big party to celebrate that Simba was born. Mufasa holds the baby lion up to show him the mountains. Then Simba is chased by hyenas. Scar, who’s bad, tries to kill Mufasa and Simba. Then Timon and Pumbaa sing a song.” And on and on.

This is the model that most film reviewers adopt, at least in the United States — paragraph upon paragraph of this happens, then that happens, and to sum up, four stars. The better ones use plot as a sort of trellis to hang their observations on, making little asides about the psychology or the camerawork or the acting as they slog through a sequence of events.

None of them, though, has ever figured out the simple truth that has infused LaSalle’s criticism for decades: Readers don’t need or want a detailed plot synopsis at all! The amount of data we require on that front is vanishingly small. It’s a family drama, and Carey Mulligan gives a fascinating performance for such-and-such a reason is the important information; while rifling through a chest of drawers, she finds her father’s letters to his second family is not. Critics who devote their reviews to plot are scrambling to fill column inches because they don’t have enough engaging thoughts of their own. LaSalle doesn’t have that problem.

I admired this aspect of LaSalle’s criticism for years before realizing that I had semi-consciously adopted it myself. Reviewing opera can be a tricky business, because most of the time you’re writing about a piece that some of your readers have seen many times, while some know nothing about it at all. (Writing about a new piece, which film and theater critics do all the time, is an all-too-rare treat on my beat.) Laying out the plot of La Bohème in detail is boring, but omitting it entirely is snobbish and off-putting to most readers. There has to be a middle ground. And so, at first intuitively and then deliberately, I began imitating LaSalle, telling readers just enough so they understood what the rest of the review was about, but not so much that their eyes glazed over. It felt great. I felt like I was walking in the footsteps of a master.

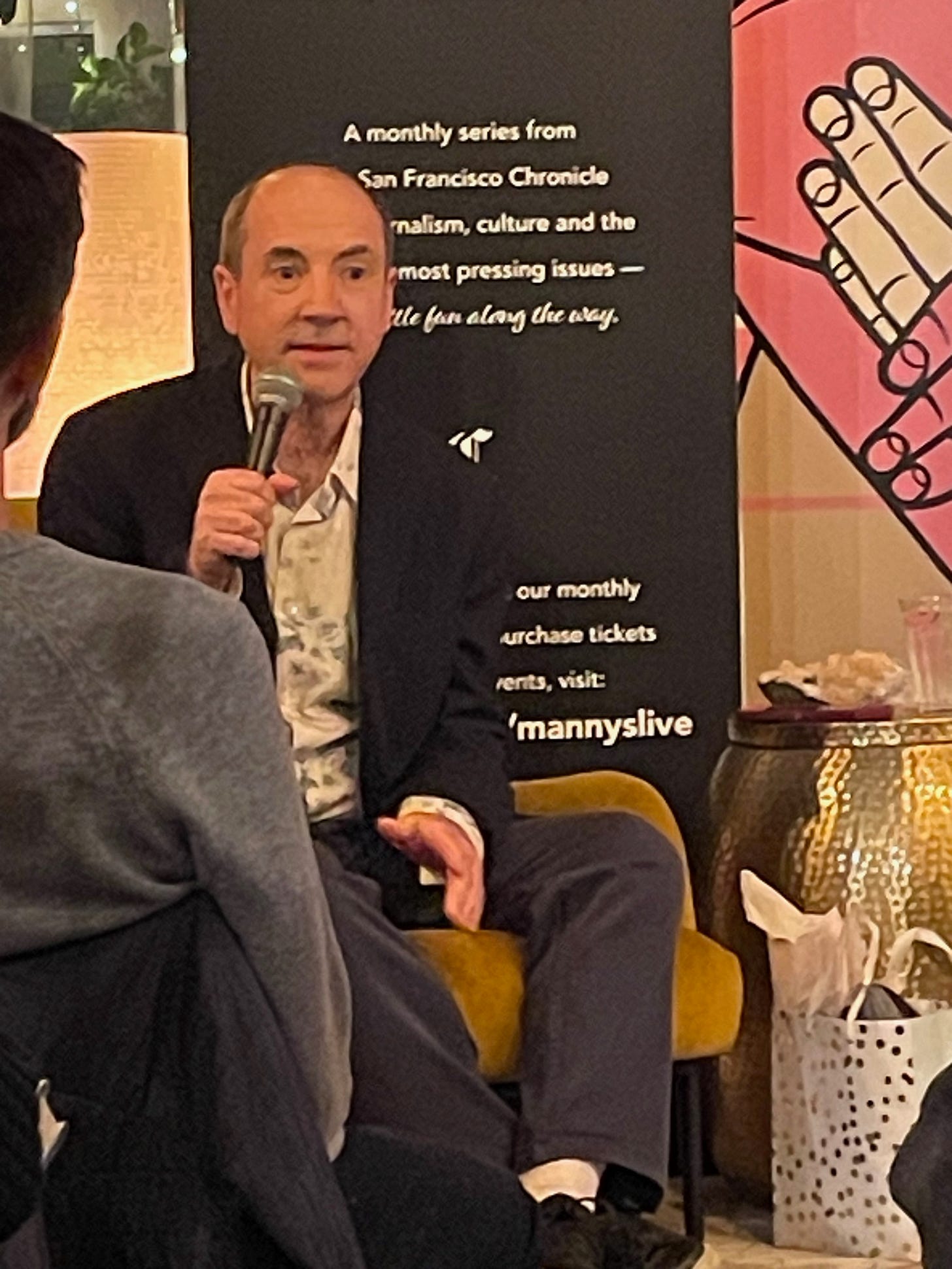

During a public Q&A last week with Mariecar Mendoza, the Chronicle’s senior arts and entertainment editor, LaSalle said he was retiring because it was “not a job for an old guy.” I don’t know that he’s actually an old guy yet — although he is, and always will be, six months older than I am. But there is a danger, especially in connection with pop culture, of observers aging out of a full understanding of the field. The day arrives when the critic thinks “this movie is no good,” but the truth is “you don’t get what this is about, do you, grandpa.” It’s entirely in keeping with LaSalle’s abilities — his perceptiveness, his modesty, and especially his understanding of human psychology and the passage of time — to have spotted that hazard on the horizon, and to have evaded it so gracefully.

Cryptic clue of the week

From Out of Left Field #247 by Henri Picciotto and me, sent to subscribers last Thursday:

Belly button, or, in French, “ligature” (5)

Last week’s clue:

Concert at a Los Angeles neighborhood provides plenty of power (9)

Solution: GIGAWATTS

Concert: GIG

a: A

Los Angeles neighborhood: WATTS

plenty of power: definition

Coming up

There are no musical events on the horizon worth plugging. Stay home, make a fire, read a book.

Loved this description of LaSalle's writing style - as well as Kosman's writing style! which is why I subscribed. Refreshing to read good writing!

Very satisfying to read a spot-on encapsulation of what makes LaSalle's writing so enjoyable. I'm in awe of both your ability to be so perceptive — and entertaining — on a dime. LM1s for the both of ya!