Ship of sages

A glorious new multimedia work from the prodigious imagination of artist William Kentridge took the stage in Berkeley

The cargo ship Capitaine Paul-Lemerle, converted to accommodate human refugees, sailed out of Marseille on March 24, 1941, headed for Martinique. The passengers included Claude Lévi-Strauss, André Breton, and the Communist novelist Victor Serge, which might seem like quite enough brain power for a single ocean liner to accommodate.

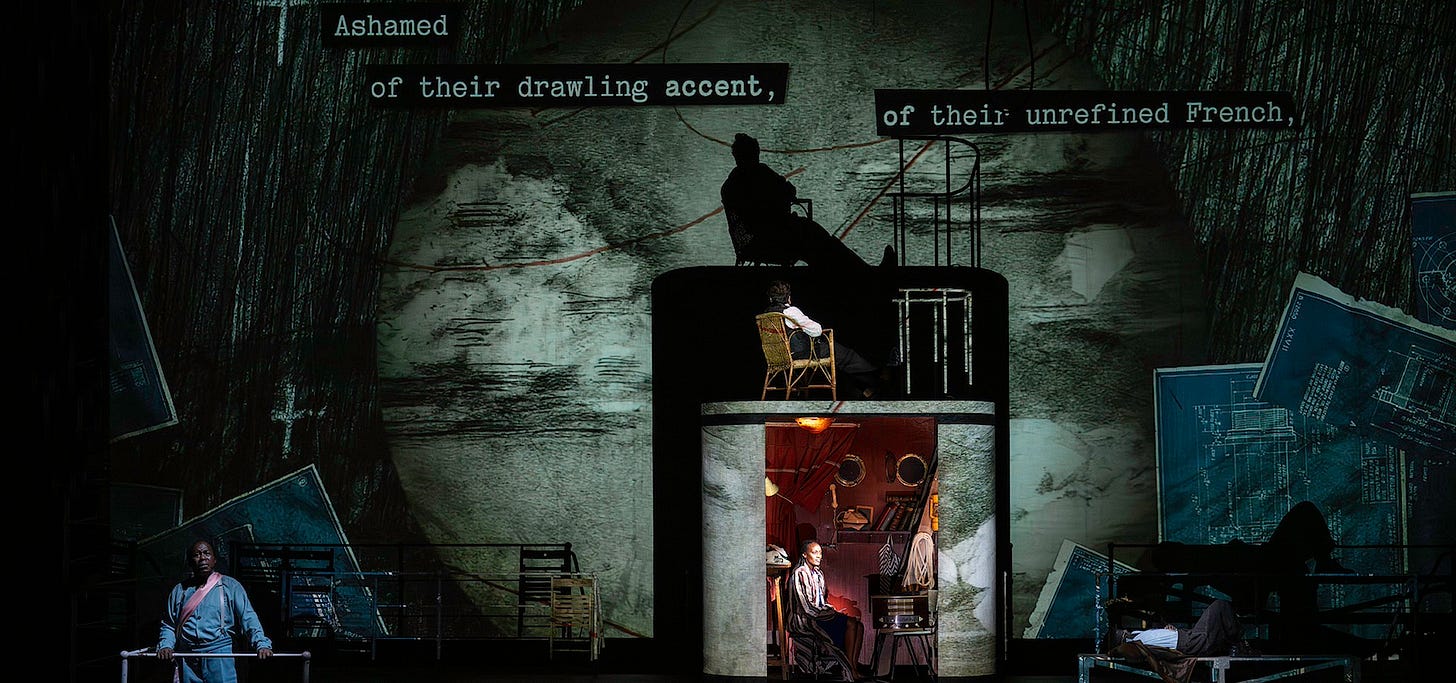

But The Great Yes, The Great No — the extravagantly rich, funny, and beautiful new stage work by the South African artist William Kentridge, which came to Cal Performances for three performances over the weekend — adds to the passenger manifest with canny, anarchic glee. Like some kind of genial salon host, Kentridge brings on board the Martinican poet Aimé Césaire, the philosopher Frantz Fanon, the sisters Paulette and Jeanne Nardal (architects of the Négritude movement), Leon Trotsky, and more.

With everyone in place, the audience embarks on a voyage that — in spite of the political shadows of exile, colonialism, and war that loom over everything — can only be described as a pleasure cruise. Friday’s opening performance was a whiz-bang circus full of music, dance, surrealist visuals, realist visuals, verbal aphorisms, and much more. Kentridge and his collaborators rarely work within a single modality if they can hopscotch across many at once.

Running through the piece is a multifarious reflection on physical and philosophical dislocation. “A refugee,” we are reminded early on, “is an unwilling tourist,” and The Great Yes, The Great No explored the subject from all angles. A chorus of seven women intoned composer Nhlanhla Mahlangu’s gorgeously blended harmonies. Actor Nancy Nkusi recited long swatches of Césaire’s poetry — a fragrant etude of homesickness for Martinique — with unearthly grace. Dancers with oversized photographic masks turned the Nardal sisters into buoyant performers; Breton was embodied in double form by two actors; two Josephines — Baker and Bonaparte — joined forces for a duet of Schubert and hot jazz.

Presiding over it all was actor Hamilton Dhlamini as the mercenary ship’s captain, leavening his cynicism with tart, tender wit. “Where you are coming from, you will not be missed,” he tells the passengers. “Where you are going, you will not be welcome. But while you are on board my ship you will be treated well.”

The Great Yes, The Great No is rooted in a complex network of historical specificity, but like all powerful art it speaks to concerns that resonate far beyond that. Nowhere was that more evident than at the moment when the captain addressed his passengers — and us — to proclaim: “Stop hoping things will get better! If they do get better, they won’t get better for you!”

Elsewhere:

Steven Winn, San Francisco Chronicle/SFCV: “What transpires in his new work — at sea, in life, in history, in the hearts and minds of the refugees and in ours as their witnesses — is poetic, mysterious, tragic, surrealistic, comical, stirring and furrowed with keenly felt life.”

Gary Kamiya, Kamiya Unlimited: “There are visual and musical fireworks aplenty in The Great Yes, The Great No, but no intellectual ones. In fact, nothing even remotely resembling a narrative, let alone a clash of ideas, emerges from this 90-minute kaleidoscope.”

Michael Strickland, Civic Center: “There were so many unfamiliar references and digressions that I found it impossible to make much sense of the theatrical work, but it did not matter because there was so much to absorb and enjoy.”

With friends like that…

The title of Yasmina Reza’s 1994 exuberant comedy “Art” (the sarcastic scare quotes are an essential part of the name) constitutes a deft and characteristically subtle head fake. There’s a painting at the center of the piece, a canvas that may or may not be entirely white and that certainly lacks any obvious features aside from a few faint diagonal lines. But the painting is a MacGuffin, and the play, which opened Saturday night in a fine new production at Shotgun Players, isn’t about art at all.

Or rather, it’s about art as a vehicle for our opinions: what we value and why, how we reach and act on those decisions. And even that, in turn, is only a way station on the path to Reza’s true subject, which is friendship (particularly, it should be said, male friendship). Must our friendships be predicated on an alignment of values (esthetic, philosophical, characterological) and if so, how closely must they align? Or, to descend from the general to the specific: If your good friend drops an exorbitant sum of money to buy a painting that is obviously shit, then why are you friends with him in the first place? But conversely, what kind of friend enforces strict esthetic codes? And for those outside the fracas, who wants friends that squabble over stuff like this? But then again, what use is a friend who never disagrees with you about anything?

Over the course of 90 intermissionless minutes, the three characters of “Art” (played with shape-shifting virtuosity by Woody Harper, Benoît Monin, and David Sinaiko) mud-wrestle their way through this treacherous terrain, each one gaining the upper hand in turn for a minute or two at a stretch. You watch in wonder, thinking, “He’s right, you know” and “Christ, what an asshole” over and over in different permutations. There are long monologues of hilarious insufferability and pinball-like volleys of intellectual one-upmanship, all of which might be hard to take if Reza herself weren’t so funny and godlike in her view from above.

Director Emilie Whelan starts things off a bit too didactically, with a brief glimpse of all three men in their primal ape-like form — clad only in their underwear, thrashing around to the head-banging strains of Rage Against the Machine — before they dress up and begin arguing about deconstruction. Once the play begins in earnest, though, she charts the play’s dynamic shifts with sure-footed mastery, and the small Shotgun stage makes the drama feel both intimate and compressed, as if the characters were sentient kernels of popcorn bouncing around in a particularly close space.

“Art”: Shotgun Players, through April 12. www.shotgunplayers.org.

Elsewhere:

Lily Janiak, San Francisco Chronicle: “The play…bears one key resemblance to Berkeley Rep’s currently running (and spectacular) Uncle Vanya: Both derive their dramatic and comedic juice from how insane everyone drives everyone else while some mysterious magnetic force just won’t let them leave the room.”

Caroline Crawford, Bay City News: “The acting is superb. Director Emilie Whelan regulates the onstage temperature so that Marc or Yvan almost relent to validate Serge— until they don’t, and the collective upset grows.”

Reality bites

Nobody Loves You, the cheerful pop musical that opened March 12 at ACT, offers a knowing satire of the kind of reality-TV romance shows exemplified by “The Bachelor,” “Love is Blind,” and so forth. You might suppose this is a vein of popular culture that doesn’t urgently need satirizing, and you wouldn’t be wrong, exactly. But don’t be too quick to dismiss the superficial pleasures of this concoction by playwright Itamar Moses and composer Gaby Alter, or you’ll miss the deeper pleasures lurking beneath its surface.

In fact, you’ll be replicating the error of Jeff (A.J. Holmes), the weedy, arrogant philosophy grad student who enlists in the titular TV show to expose its fundamental bad faith (and find a dissertation topic), only to find that things are more complicated and more interesting than he imagined. In a cultural setup like reality TV, carefully constructed to co-opt literally any human emotion and turn it into fodder, burning everything to the ground is no simple task.

Nobody Loves You both makes and exemplifies that point. The jokes and the musical numbers are generic but effective, in the manner of a top-drawer sitcom, and director Pam MacKinnon consistently resists the urge to underline any of it. Instead, the show coasts along on the spangly charisma of its cast (particularly Jason Veasey as the Teflon-coated, long-legged host of the show) and production design that makes cotton candy and neon seem implausibly appealing.

Nobody Loves You: ACT, through March 30. www.act-sf.org.

Elsewhere:

Lily Janiak, San Francisco Chronicle/SFCV: “TV show host Byron (Jason Veasey) isn’t just oblivious. He adores the bubble he’s built for himself. He would be 100% fulfilled if he spent the rest of his life improvising backup singing that repeats everything his contestants blather; in his mind, content is content.”

Karen D’Souza, Marin Independent Journal: “…from the staged meet-cutes to the unctuous host Byron (a wonderfully cheesy turn by Jason Veasey), the trappings here are so fun that it distracts you from the hackneyed bits, at least at first. Unfortunately, the uneven 105-minute show has a few more songs (largely forgettable) than it can buoy through sheer exuberance.”

Jim Gladstone, Bay Area Reporter: “Pam Mackinnon's fleet, fizzy direction…zip[s] audiences through a series of parodic hot takes and satirical sallies on today's relationships, mores, and media.”

Quick hits

• Conductor Elim Chan came to Davies Symphony Hall this week to conduct the San Francisco Symphony in an all-Tchaikovsky program: excerpts from Swan Lake on the first half, followed after intermission by the Pathétique Symphony. Chan is an interpreter of great physical mastery as well as interpretive imagination, and even a program as mundane as this one had its rewards.

In particular, I love the way Chan handles an orchestra as if she were driving an enormous harvester, summoning up great masses of instrumental sound and then directing them exactly where they should go. On Thursday afternoon, the Swan Lake movements featured solos of great delicacy and eloquence from several members of the orchestra — oboist Eugene Izotov and harpist Katherine Siochi above all — but it was the big, sweeping dramatic episodes that proved most effective. In the Pathétique, Chan drove the implacable third movement onward and upward in a perfectly paced movement-long crescendo, then went directly into the finale so as to prevent the explosion of applause that always erupts there. It was a splendid display of authority.

Elsewhere

Michael Zwiebach, San Francisco Chronicle/SFCV: “Chan clearly works from a detailed conception of the score, but what the audience sees is a conductor who is as communicative as a dancer.”

• The San Francisco Symphony announced details of its 2025-26 season this week, and I returned to my old stomping grounds at the San Francisco Chronicle to offer some dyspeptic thoughts on the subject. My column is here, and Lisa Hirsch’s excellent reporting is here.

Cryptic clue of the week

From Out of Left Field #259, a puzzle by guest constructor Sean M. L. McAfee:

Minor star appears in World War Five (5)

Last week’s clue:

Some funds provided by Tom and Johnny (5,4)

Solution: PETTY CASH

Some funds: definition

Tom: PETTY

Johnny: CASH

Coming up

Jan Lisiecki: A prelude, by definition, comes before something else — or does it? Chopin, most famously, cast doubt on that proposition with his Op. 28, a set of 24 piano preludes in every major and minor key that deviated from the model of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier by omitting the fugues those preludes were supposed to introduce. The young Canadian pianist Jan Lisiecki explores this idea in an all-prelude recital including Op. 28 along with music by Bach, Messiaen, Szymanowski and more. March 20, Herbst Theatre. www.sfperformances.org.

California Symphony: Slowly but ineluctably, the music of the midcentury Polish composer Grażyna Bacewicz has begun to populate our concert halls more regularly. Donato Cabrera leads the orchestra in a performance of her 1949 Piano Concerto, with David Fung as soloist. Also on the program is the world premiere of Fantasia for Strings by composer-in-residence Saad Haddad. March 22-23, Lesher Center for the Arts, Walnut Creek. www.californiasymphony.org.

I can't disagree with any particular point you make about "Art," and yet I found myself puzzled by the play. I didn't find it as funny as anyone else in the audience tonight, though references to deconstructionism got a giggle or two out of me. I found it somewhat distracting that Yvan is straight - he is marrying a woman - but the actor's speaking and gestures were, to my eye and ear, gay coded.

Glad you could make it to NOBODY LOVES YOU!