Walking wounded

Twenty-five years after its San Francisco Opera premiere, Dead Man Walking remains a musical and dramatic triumph

When Jake Heggie and Terrence McNally’s opera Dead Man Walking had its world premiere at the San Francisco Opera in 2000, I took to the pages of the San Francisco Chronicle and pronounced it a “masterpiece.” I did it with the requisite bravado, but not without a certain amount of trepidation. That the opening night had come off superbly — especially from a first-time opera composer whose work had thus far been confined to art songs and cycles — was undeniable. But no one with any knowledge of operatic history would have imagined that that meant Dead Man Walking would go on to take its place as an international repertory staple or the most widely performed new opera of the 21st century.

It did, though! That’s exactly what it did. And deservedly so.

To understand why — to get a full immersion in the work’s moral complexity, theatrical flair, and musical richness — you could hardly do better than catch up with the 25th-anniversary production that opened Sunday afternoon at the San Francisco Opera. It’s a revival and a homecoming, as well as a magnificently argued case for the splendors of this opera.

Dead Man Walking, which is based on real-life events, is framed by two dark and incontrovertible facts. It opens with a rape and double murder, staged so as to disturb your sleep for days afterwards. It ends with the execution by lethal injection of Joseph De Rocher, the convicted perpetrator of those crimes.

In between, though, everything is fluid, elusive, and hard-fought. Sister Helen Prejean, the New Orleans nun who starts up a casual correspondence with the prisoner and winds up being his spiritual advisor, grapples with a host of doubts while clinging to a few basic truths such as her religious calling and her opposition to the death penalty. (The opera, like director Tim Robbins’ film before it, is based on Sister Helen’s 1993 memoir of the same name.) She believes that Jesus calls on her to love the prisoner unconditionally, but struggles to fulfill that demand as she would wish. De Rocher, meanwhile, wants love and forgiveness (perhaps even a pardon from the governor), but remains reluctant to acknowledge his own culpability. The parents of the murdered teenagers have allowed their real and unbearable grief to fester into bloodthirsty rage. The prisoner’s family — a soulful, unlettered mother and two bewildered tweener brothers — can barely begin to grasp anything beyond their own pain.

It’s a lot to take on, as each glimpse of moral certitude seems to give way almost immediately to its opposite. McNally’s terrific libretto — by turns comic, sentimental, probing, and profane — gets us part of the way there. But it’s Heggie’s score above all, conducted with powerful assurance by Patrick Summers, that helps the audience connect all the dots, by letting the music speak the emotional truths the characters can’t always register through words.

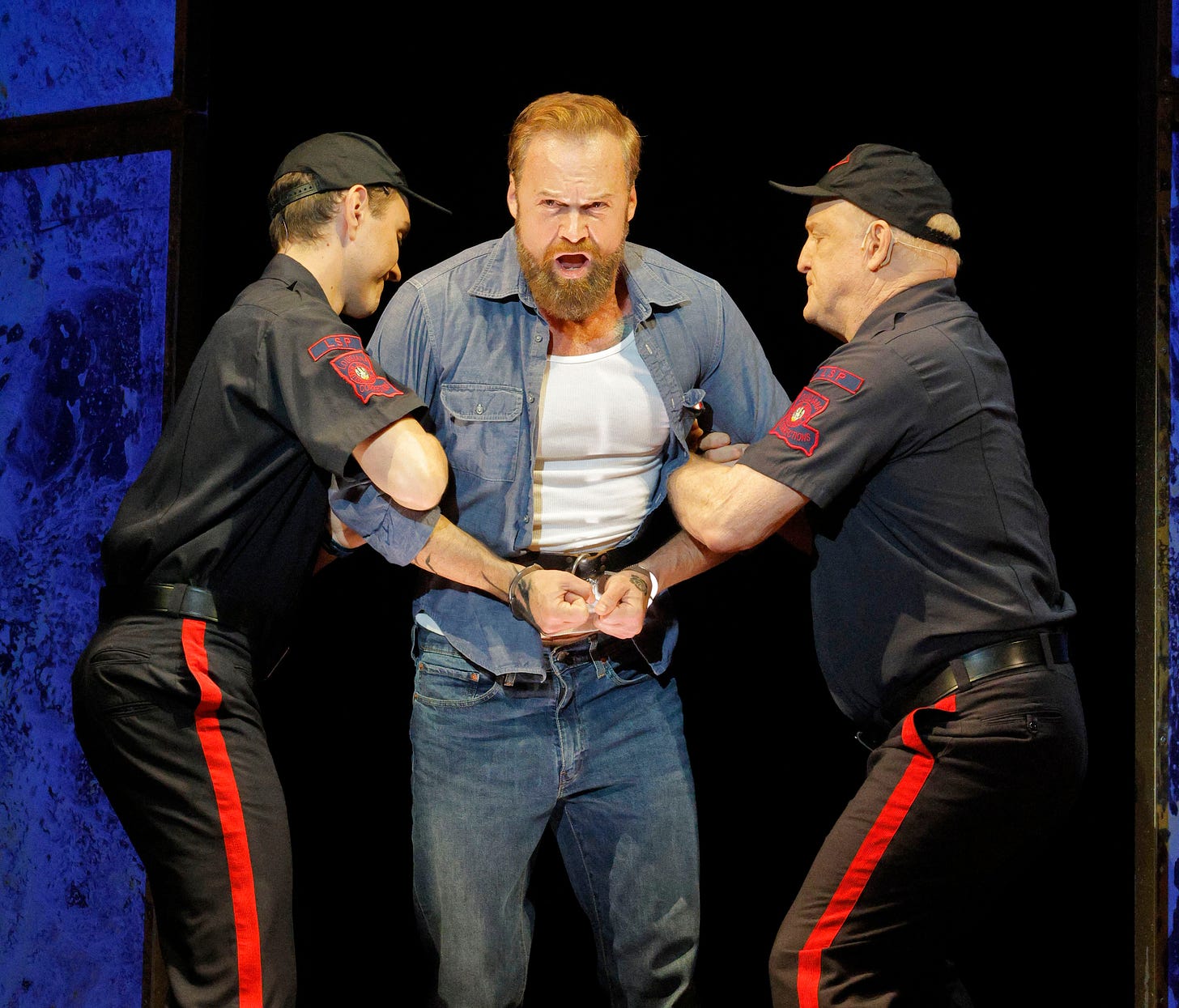

Sister Helen (mezzo-soprano Jamie Barton, in a gorgeous performance marked by vulnerability and wit) gets an extended soliloquy near the beginning of the opera that tells you everything you need to know about her life and aspirations; a subsequent duet with her associate Sister Rose (soprano Brittany Renee) lays out her trepidation in tender, eloquent phrases. As De Rocher (portrayed with heroic stamina and specificity by baritone Ryan McKinny) gradually frees himself from his self-protective emotional carapace, his music softens and broadens, becoming more luminous in the process. In a quartet for the bereaved parents, led by the electrifying baritone Rod Gilfry, the vocal lines eddy and overlap to conjure up a comfortable daily family life brought to a sudden and brutal end.

It's not the most central scene, yet perhaps the opera’s most unforgettable episode — the one that has lingered most clearly in the memories of anyone who was at the 2000 premiere — is the appearance of the convict’s mother, Mrs. Patrick De Rocher, before the Louisiana Parole Board. The role was created by the great mezzo Frederica von Stade, and has now been fittingly inherited by Susan Graham, who sang the role of Sister Helen for the first and only time during the premiere.

Her words are stark and simple (“Please don’t kill my boy”) and the music matches them, phrase by halting phrase. To Mrs. De Rocher, all of this is both lacerating and incomprehensible. How can such a thing be happening — here, now, to her and hers? There’s no consolation we, or anyone else, can offer her. Her brokenness reflects our own.

Dead Man Walking: San Francisco Opera, through Sept. 28. www.sfopera.com.

Elsewhere:

Lily Janiak, San Francisco Chronicle: “As Joseph’s mother, Susan Graham…sings the line ‘Haven’t we all suffered enough?’ three times at her son’s final parole board hearing, sounding softer and less certain with each repetition. It’s a canny embodiment of the opera’s insistence on seeing everyone’s point of view.”

Nicholas Jones, SFCV: “Much of the story is told in monologues, appropriately illuminating the isolation fostered by guilt, incarceration, and death row. But there were welcome moments when characters connect intimately, particularly in vocal duets. A long duet between the exhausted Sister Helen and her fellow nun, Sister Rose — sung with aching tenderness by soprano Brittany Renee— was especially beautiful.”

Matthew Travisano, Parterre Box: “As is the case with a lot of mainstream contemporary operas, Heggie’s writing tends to be the same from scene to scene. A vocal line will start in the middle voice, then build to a ringing crescendo into the singer’s upper range, then the tension is let out and we start over again.”

Gary Kamiya, Kamiya Unlimited: “Dead Man Walking is not a political work. It is much too profound to be reduced to the merely political. But it was impossible to watch it and not reflect on our current grim political moment, when the all-too-human forces of unbridled rage and the desire for revenge — understandable ones, as this work acknowledges — have received the highest imprimatur…”

Cornball

Shucked, the Broadway hit whose touring company rolled into the Curran Theatre last week, might just as well have been titled Dad Jokes: The Musical. There’s a simple story, which is all about corn, and a bunch of reasonably hummable (if not very distinctive) songs. But the point of the exercise is to pepper the audience with one-liners and puns at such a rapid-fire pace that you can’t avoid having fun. Not a minute goes by without some kind of punchline whizzing past your head. For folks of my generation, the relevant esthetic is reminiscent of Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In; no doubt other models have come along in the intervening decades. (Edited to add: Evidently the more direct model is Hee-Haw, which I confess I’ve never seen.)

The jokes come in three broad categories. There are straight-up groaners (“A butcher should introduce his wife by saying ‘Meet Patti’” or “A paper airplane that can’t fly is just…stationary”). There are mildly risqué offerings from the high school locker room (“Never arm-wrestle with a guy who’s been single for a long time”). Best and rarest are the M.C. Escher jokes, which somehow manage to wind up somewhere back of where they began (“Marriage is two people getting together to solve problems they didn’t have before they got married” or “If a person didn’t know any better, that person wouldn’t be me”).

I can’t promise you’ll enjoy Shucked as much as I did, but you already know whether this is the kind of thing that will tickle your funny bone or leave you squirming with annoyance and boredom. (On returning home, I regaled my wife with a long list of my favorite jokes from the show, and every single one was met with stony silence. I probably didn’t tell them right.) In addition to all the gags, the production boasts a first-rate cast of singer-dancer-actors, all of whom work at full throttle to show the audience a good time; this is the kind of musical in which every stage entrance or exit happens at a sprint. It’s largely empty calories, but by God it’s irresistible.

Shucked: Curran Theatre, through Oct. 5. www.broadwaysf.com.

Elsewhere:

Lily Janiak, San Francisco Chronicle: “Resistance is futile. Shucked knows that, deep down, you’re just a puerile punster looking for instant gratification, and all it takes is a bombardment of double entendres and one-liners for your true self to rear her yukking, dopey grin.”

Linda Hodges, Broadway World: “Who knew that an embarrassing number of corny one-liners (anyone old enough to remember the variety show Hee Haw?) scattered across two acts could fuel such a fizzy night of theater magic and fun?”

Drunkard’s dream

The Reservoir, which opened the new season at Berkeley Rep last week, is a semi-autobiographical account of playwright Jake Brasch’s struggle toward sobriety after leaving drama school. Right away you can see the problems.

Chief among them is that the recovery memoir is perhaps the most unvarying and predictable art form known to humankind. The beginning is always the same, a crisis or some particularly vicious bender that sets our protagonist on a path away from substance abuse. The ending, too, is foreordained: If the story doesn’t move the addict some significant distance from where we first met them (i.e., to a full, though necessarily tentative, recovery), then what justification is there for demanding our attention? Along the way there will be a relapse, there will be promises made and broken, and some loved one will shake their head in dismay and sigh, “I can’t do this anymore.” There’s a checklist to this kind of undertaking, and we all know what it contains.

That’s not to say there can’t be minor variations in the template, and every once in a long while an example that transcends the limitations of the form through sheer artistic genius. (Shout-out to The Lost Weekend, the unmatched and perhaps unmatchable pinnacle of this genre.) But for the most part, those details are visible from up close, which, not coincidentally, is where the memoirist is; to an outside observer, the stories are all largely indistinguishable.

The point of interest in The Reservoir is not Josh, the protagonist (Ben Hirschhorn, in an energetic but oddly opaque performance). It’s his four grandparents, each of whom embodies an entire rich and unpredictable world apart from Josh’s formulaic troubles. On the Jewish paternal side are the exuberant and profane Shrimpy (Peter Van Wagner), who is still exulting in tales of his youthful sexual escapades as he prepares for his second bar mitzvah at age 83, and Bev, a dark, furious dynamo of resentment and wisdom in a virtuosic performance by Pamela Reed. On the Nebraska-born gentile side are the loving, dotty Irene (Barbara Kingsley) and her taciturn, scowly, Republican husband Hank (Michael Cullen).

Every moment we spend with these four is a delight; they’re funny, fond, and imbued with great psychological specificity. A play about them would be something memorable, especially since death and Alzheimer’s are gunning for all of them. But Josh insists on obscuring our view of them by commandeering center stage. Worse yet, Brasch makes them supporting characters in his own much less interesting narrative. How do you look at an old woman devastated by Alzheimer’s and think, “This is a metaphor for my own alcohol abuse”?

The Reservoir: Berkeley Rep, through Oct. 12. www.berkeleyrep.org.

Elsewhere:

Lily Janiak, San Francisco Chronicle: “If you’re fighting addiction, as playwright Jake Brasch has, it’s probably therapeutic to write or witness something like his semiautobiographical The Reservoir. But if you’re not, attending Berkeley Repertory Theatre’s production feels like enabling someone else’s self-indulgence.”

Jean Schiffman, Bay City News: “The Reservoir is an unsparingly truthful play. Brasch has a truly theatrical insight into the humor and heartbreak of the human condition.”

Victor Cordell, Cordell Reports: “Full of strong performances of well-differentiated characters, this dark but funny semi-autobiography holds the attention throughout. The play strengthens as it progresses, as Josh’s unappealing self-indulgence is somewhat supplanted by touches of humility and redemption in Act 2.”

That’s settled!

The best news out of Davies Symphony Hall this week had nothing to do with Friday night’s season-opening gala. No, it was something that happened a few hours before that, when the orchestra’s musicians and management surprised everyone by suddenly reaching a contract agreement after years of increasingly acrimonious negotiations over salary, benefits, and so forth. The settlement came on the heels of a vote by the musicians’ union to authorize a strike.

In the Chronicle, Aidin Vaziri and Tony Bravo have more information, including the detailed dollar amounts that don’t mean much to the rest of us. The takeaway is that neither party seems fully satisfied, yet both are willing to sign on the dotted line. That’s a big improvement from just a week ago, and generally the sign of a successful compromise. May it continue so.

The gala concert itself was brisk and vacuous, as such events usually are. Jaap van Zweden, the guest conductor, favors sharp phrasing and blunt rhetoric, which made the gorgeous, mechanized tick-tock of John Adams’ Short Ride in a Fast Machine a perfect curtain-raiser, and made Respighi’s Pines of Rome sound even more brutally nationalistic than usual.

Yuja Wang was the soloist for Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1, and because she always understands the assignment, she used her extraordinary keyboard technique to inject some much-needed lyricism into the overall bombast. More delightful were her encores: the “Dance of the Four Swans” from Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake, arranged by Earl Wild; Schubert’s “Gretchen am Spinnrade” as arranged by Liszt; and Vladimir Horowitz’s finger-busting “Carmen” Variations, a favorite showpiece of Wangs which on this occasion, the press department tells me, included her own improvisations. Truly astonishing stuff.

Elsewhere:

Lisa Hirsch, San Francisco Chronicle: “That Wang is a great virtuoso goes without saying, but even so, the concerto’s bombastic opening, with its gigantic chords, left you wondering how she could generate such thunderous power and volume while hardly moving.”

Steven Winn, SFCV: “Performed by the Symphony in May along with the composer’s Fountains of Rome, Pines was fresh in the players’ musical memories. With that and van Zweden’s energetically engaged conducting, an expansive, luscious, and dramatic performance unfolded.”

Cryptic clue of the week

From Out of Left Field #285 by guest constructor David Ellis Dickerson, sent to subscribers last Thursday:

Wisconsin city reporter’s wood den (3,6)

Last week’s clue:

Mountain boasts high-ranking types (6)

Solution: ALPHAS

Mountain: ALP

boasts: HAS

high-ranking types: definition

Coming up

• San Francisco Symphony: With the opening festivities out of the way, the Symphony now gets its regular concert season rolling with the help of guest conductor James Gaffigan. Gaffigan will lead the orchestra in an all-American program bookended by music from two leading African American composers, Carlos Simon and Duke Ellington. Also on the menu are two George Gershwin classics, An American in Paris and the Piano Concerto in F with soloist Hélène Grimaud. Sept. 18-20, Davies Symphony Hall. www.sfsymphony.org.

• Chanticleer: Another all-American season opener comes courtesy of Chanticleer, the renowned men’s chorus whose repertoire extended from Renaissance polyphony to the modern day. The centerpiece is a commissioned premiere by composer Trevor Weston examining the connections between traditional American hymnody and African American spirituals. Also on the program, led by music director Tim Keeler, are samples of barbershop music, bluegrass, folk songs and jazz. Sept. 20-28, locations in Berkeley, Sacramento, Mill Valley, Santa Clara, and San Francisco. www.chanticleer.org.

I saw the production of Dead Man Walking in 2000, and was stunned by it. By the same token, I was convinced at the time that I could never go through it again - and 25 years later, I feel the same way. It's like witnessing a public execution. Not something I can do again. Stunning opera, and everyone should see it. Maybe not twice.

A confession: I did not think that much of DMW in 2000, and last night I discovered that I was wrong, wrong, wrong. It is indeed a great opera and fully deserves its reputation and many many (82!) productions.

I chalk it up to not having heard enough contemporary opera at that point to properly judge it. The music is great, it's beautifully orchestrated, the libretto is strong, and Heggie writes so very well for the voice.